Allensworth is the only town in California that was founded, financed, built, populated, and governed by African Americans. This pioneering venture in the ongoing struggle for freedom and opportunity resulted from the vision and determination of Lieutenant Colonel Allen Allensworth. Today, a hundred years after its heyday, visitors to the historic townsite are still inspired by the Colonel’s ideals and accomplishments and by his town that refuses to die.

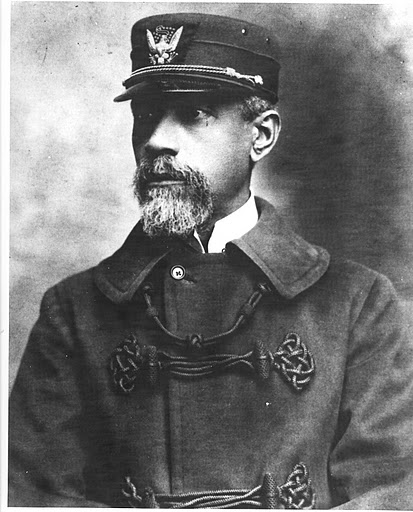

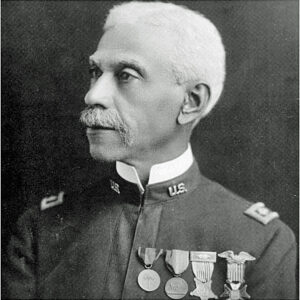

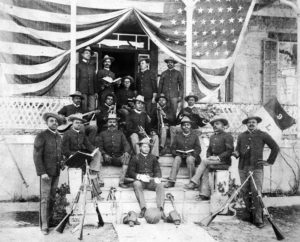

Born into slavery in 1842, Allen Allensworth learned to read and write as a young man. He eventually escaped slavery by joining the Union forces during the Civil War. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy, and quickly rose through the ranks. In 1886, after civilian careers in teaching and business, and earning a doctorate in theology, he re-entered the military as the U.S. Army’s first Black chaplain, guiding the spiritual well-being and moral education of the soldiers serving in the 24th Infantry, one of several army units comprised of all African Americans (the renowned Buffalo Soldiers). Twenty years later, Lieutenant Colonel Allensworth retired, the first African American to achieve such high rank. His vision and vigorous leadership continued into the next phase of his life.

In a series of lectures he delivered, Allensworth stressed the importance of self-determination and urged African Americans to develop economic, social, cultural, and political self-sufficiency. During his extensive travels, he noticed thousands of Blacks migrating to California in order to free themselves from systemic prejudice — the South’s segregation policies and the North’s discriminatory policies and practices.

He moved his family to Los Angeles, the seeming land of opportunity for his dream. But it was in the southern San Joaquin Valley that he found all the right elements for pursuit of that dream — affordable land, rich with good soil, ample water, and a railroad stop that promised transportation and freight business.

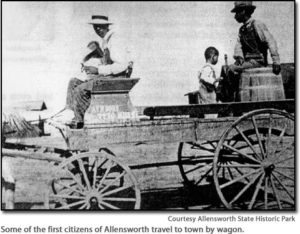

He joined forces with other like-minded individuals, including Professor William Payne, Rev. William Peck, Rev. John W. Palmer and Harry A. Mitchell, to form the California Colony and Home Promoting Organization. With Colonel Allensworth as president, the group purchased 800 acres and filed a township site plan in August 1908 for a town called Allensworth. It would be an all-Black community where families could prosper free from the crippling effects of discrimination and unfair governance.

The town’s founders highly valued education, scholarship, self-governance, and hard work. Those who shared this vision were attracted to Allensworth and contributed to its growth. Within a year, thirty-five families called Allensworth home.

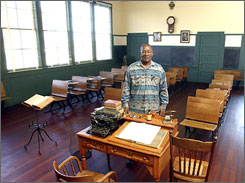

Artesian wells supplied water to the growing town and farming operations, and the Allensworth Rural Water Company was formed to provide community water services. The town built a beautiful schoolhouse and hired Professor William Payne as teacher. Mrs. Josephine Allensworth, the Colonel’s wife, started a library with books donated by Colonel Allensworth and other residents. It was Tulare County’s first free library.

The town expanded to include a post office, several businesses, a hotel, churches, and two general stores. The American Dream seemed to be thriving in Allensworth, and the Colonel proposed the establishment of a Vocational School, a “Tuskegee of the West,” to provide higher education.

But, starting in 1912, a series of circumstances created setbacks for the Allensworth community. The artesian wells dried up and a legal battle ensued with the Pacific Farming Company over water rights. Though the people of Allensworth eventually prevailed, water shortages continued to plague the area, a serious problem for the town’s agriculture-based economy.

A second setback occurred when the Santa Fe Railroad built a spur line to Alpaugh, just 7 miles away, and discontinued its stop at Allensworth, taking away the lucrative freight loading business and greatly reducing income for Allensworth.

Then disaster struck in September, 1914: Colonel Allensworth died suddenly when he was struck by a speeding motorcyclist as he crossed the street in Monrovia, where he was to speak at a church.

Shocked at the loss of their dynamic leader, the community nevertheless rallied and two new leaders took up the fight for a vocational school, a venture that promised a new source of income for Allensworth. Things seemed to be going well until the State legislature declined the project, handing a bitter defeat to the town.

Some people held on living there, trying new ideas and innovations to keep the town alive, but gradually most people moved on and only a handful of dilapidated buildings remained. A water crisis occurred in the mid-nineteen sixties when dangerous levels of arsenic were found in the town’s drinking water supply and a mass exodus began.

All hope of reviving the town seemed to be lost. Buildings were torn down as residents fled. But in that turmoil, two brothers saw the face of opportunity. George Pope and his younger brother Cornelius “Ed” Pope had grown up in Allensworth. As the town was being dismantled, they talked about raising public awareness of the African American experience in California and the possibility of preserving the community.

Pain, anger, and devastation following the 1968 assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King created an aching void in the heart of Ed Pope and galvanized him into action. “I had to do something . . . . And I remembered Col. Allensworth and the town he founded.”

Pope helped prepare a proposal to restore Allensworth as an historical site and he pitched it to his employer, the State Parks department. Why not make Allensworth a park to celebrate Black achievement?

A groundswell occurred as the African American community stood up and began advocating for the creation of a State historic site. The NAACP, Urban League, and Black Historical Societies from far and wide pledged their support. In the nineteen seventies the State planned to set up an historic marker, but those involved wanted much more than just a marker. They got busy. They lobbied for support from the local county Supervisors, State Senator Mervyn Dymally, and all the way up to Governor Ronald Reagan.

In 1972, the Allensworth Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1974, California State Parks acquired the 240-acre parcel of the historic townsite, and Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park was born! Since then, many of the town’s significant buildings have been lovingly restored. Though often quiet, the place comes alive for special events throughout the year that are well attended, full of activities, and supported by churches and community groups from all over California and the West.

Allensworth, a community built by African Americans, deeply rooted in values of resourcefulness, dignity, and self-determination, is the town that refuses to die!

June, 2016

” Even though California did come into the Union as a ‘free state,’ immediately thereafter laws were passed that relegated Afro-Americans to a status a little above that of a slave. Blacks could not vote[,] . . . join the militia[,] . . . attend the same schools as Whites[,] . . . frequent the same places of public accommodations as Whites[,] . . . testify against Whites. . . . Allensworth represented for its inhabitants a refuge from the White-dominated political structure and an opportunity to gain access to the land which had been denied them for so long.” — California DPR

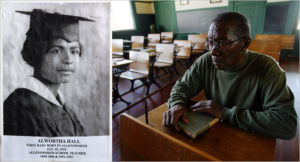

” . . . many individuals purchased lots but lived in other areas, intending eventually to settle in Allensworth. By 1912, Allensworth’s official population of 100 had celebrated the birth of Alwortha Hall, the first baby born in the town. The town had two general stores, a post office, many comfortable homes, . . . and a newly completed school.” — Kenneth A. Larson

“Over the 12 years it thrived, the town elected California’s first black justice of the peace and the first black constable. Women had an equal voice in town affairs. Farmers in the Valley shipped their crops from the Santa Fe Railroad stop here. ‘They earned $5 a day loading grains’, said park interpreter Steven Ptomey, ‘at a time when $12 a week was the average wage statewide, so that was a lot of money.'” — Associated Press

“‘I call the Allensworth pioneers “Genius People,” because they had a vision that would uplift an entire race of people,’ said Alice Calbert Royal, born here in 1923 at the insistence of her grandmother . . . ‘What I saw in this school . . . was the beauty and culture of the African American experience at the turn of the century, which is so totally opposite what they teach in the textbooks, even today.'” — Associated Press

“. . . the colony drew pilgrims like Cornelius Pope, who recalls his sense of revelation upon entering the two-room schoolhouse, where everyone was black and photographs of Abraham Lincoln and Booker T. Washington hung on the walls.. . . ‘She taught me how to read and write,’ he said of Alwortha Hall, his teacher, who was named after the town. ‘It was the first true happiness I’d ever known.'” — The New York Times

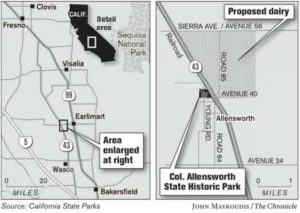

“In more recent times, Allensworth activists have fought back encroaching commercial development — like a turkey farm and an industrial food grease dump. Just last year a couple of mega-dairies . . . threatened the park. . . . After months of negotiation, Allensworth was saved — again.” — California DPR

“Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park was established for the primary purpose of providing to all Californians and all Americans an example of the achievements and contributions Black Americans have made to the history and development of California and the nation. Its aim is to perpetuate for public use and enjoyment the township called Allensworth, dedicated to the memory and spirit of Colonel Allen Allensworth, a distinguished Black pioneer of California.” — California Department of Parks and Recreation

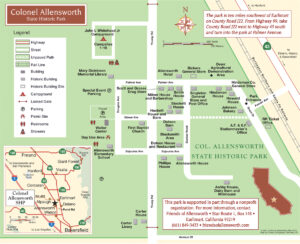

Directions:

GPS Coordinates: 35.8627° N, 119.3904° W

From Visalia, take Hwy 99 south to near the town of Earlimart. Take Exit 65/ Avenue 56, then turn west toward Alpaugh and go 7.4 miles on County Road J22 (W. Sierra Ave.) At Hwy 43, turn left (south) and proceed 2 miles to the intersection of Palmer Ave. Turn right (west) onto Palmer Ave., cross the railroad tracks, and proceed to the park entrance.

2) Battles and Victories of Allen Allensworth, by Charles Alexander (Sherman, French & Company 1914, e-version UNC-CH 2000)