Without doubt, one of the most contested and argued-about pieces of Tulare County in recent times has been the portion of the Sequoia National Forest that since 2000 has been conserved as the Giant Sequoia National Monument. The story of how these more than 300,000 acres came to be a national monument provides an almost textbook example of how land management issues are defined, debated, and eventually resolved in our society. The process can be messy, to say the least.

To understand the origins of Tulare County’s only national monument, one must know something about the Sequoia National Forest. As documented elsewhere in this website, Tulare County residents fought hard in the early 1890s to withdraw the forest lands of the Sierra Nevada from sale by the federal government and to have them instead set aside permanently as public land. This was done to protect the mountain watersheds that local farmers thought were essential to their agricultural futures. Originally a part of the immense Sierra Forest Reserve, the area was defined and named the Sequoia National Forest in 1908.

The federal agency known as the USDA-Forest Service has now managed the Sequoia National Forest for more than a century. From the beginning, national forest policy has always called for sustainable utilization of the land, with possible uses including not only watershed protection but also timber production, wildlife management, grazing, mining, recreation, and wilderness. For the first half of the twentieth century, management of the national forest system generally proceeded in a very conservative manner, with relatively little development or logging taking place. After the Second World War, however, national expectations about national forests evolved, and management of forest lands across the nation became more active. Logging, in particular, became much more heavily emphasized on most forests.

The Sequoia National Forest did not escape this trend. In the 1960s and 1970s, the forest became a major timber producer, a role that was confirmed in 1988 when the Forest Service issued a new management plan for the forest that established an annual timber production target of 97 million board feet. (This number equals approximately 18,300 miles of 1” by 12” boards.) At that time, the Forest Service was already achieving annual sales totals of over 70 million board feet.

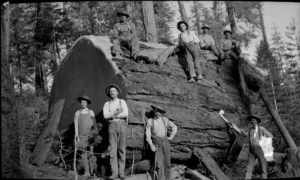

The annual production of so large a volume of lumber required that the Forest Service analyze all the forest’s acreage to determine where it could produce timber. This analysis led the forest’s managers into a consideration of the future of the forest’s thirty-three groves of giant sequoia trees. Until the 1970s, federal managers had left these groves essentially alone, allowing them to exist as de facto preservation enclaves within the larger forest. (Some of the groves had been logged much earlier by private parties prior to their being included within the national forest.)

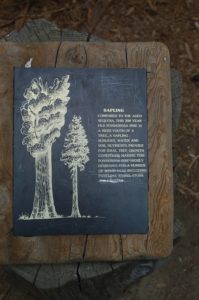

Meanwhile, scientific research taking place outside the national forests had reached a surprising conclusion: giant sequoia reproduction required forest disturbance. Put another way, this meant that giant sequoia trees, which grow only from tiny seeds, survived best when their seeds sprouted in bare mineral soil in open sunny places. In times past, the primary disturber of the conifer forests of the Sierra Nevada had been fire, and scientists concluded that fire had played an essential role in allowing young sequoias to sprout naturally and prosper. But logging is another form of forest disturbance, and the Forest Service knew that young sequoias also sprang up after older trees were cut. Out of this fact grew an idea — one that would both allow young sequoias to germinate and help meet the forest’s timber production goals — why not log in the Sequoia National Forest’s thirty-three sequoia groves?

In 1981, the Forest Service began logging in the groves, and the program lasted for five seasons before it was suspended. During those years, the Forest Service conducted thirteen timber sales covering about 1,000 acres within the groves. The intensity of logging varied from site to site, but in several areas the Forest Service authorized the removal of all standing trees except a handful of large, specimen-sized sequoias.

Logging within the sequoia groves produced sharply divided public opinion. Some appreciated the economic activity that resulted from the program. (During these years up to 240 persons worked at a sawmill in Terra Bella that received the logs cut on the Sequoia National Forest.) Others were deeply disturbed by the destruction taking place within the groves, places some saw as having near-sacred status. The controversy soon went political, and by 1986 the critics had applied enough pressure to cause the Forest Service to suspend the program.

When the Forest Service issued a new management plan for the Sequoia National Forest in 1988, however, that document called for yet higher levels of timber harvests. As a result, the battle over the forest’s giant sequoia groves intensified. Numerous organizations filed appeals of the 1988 forest plan and, under considerable pressure, the Forest Service agreed to negotiate a mediated settlement to the dispute. The resulting agreement (signed in 1990) ended logging within the groves but did not significantly reduce timber harvest on the surrounding lands.

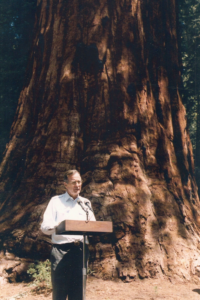

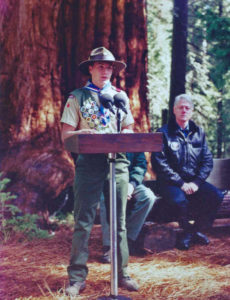

By now, the fight had gone national. The Tulare County Audubon Society actually went so far as to place a full-page ad in the New York Times challenging the management directions chosen by the Forest Service. The next several years saw congressional hearings on the subject (1991), a Forest Service public symposium on giant sequoia management (1992), and a visit to the region by President George H. W. Bush (also 1992), who signed a presidential proclamation guaranteeing that sequoias would not be cut.

The fight continued, however, with local activists like Carla Cloer, Charlene Little, and Ara Marderosian working with national environmental groups. Increasingly, the goal was to end logging both within the groves and over the larger region that surrounded them. Inevitably, a political fight of this scale reached the highest levels of government. Resolution came in the late 1990s when President Bill Clinton concluded that the preferred outcome would be one that strictly limited logging on the Sequoia National Forest.

On April 15, 2000, Clinton visited the Sequoia National Forest and signed a proclamation that designated some 327,000 acres (27%) of the Sequoia National Forest as a national monument. Making its purpose very clear, the proclamation specified that the lands in question would no longer be subject to commercial logging and that trees could be cut within the monument only for reasons of safety or ecological management.

Like the Mineral King controversy of the 1960s and 1970s, the creation of the Giant Sequoia National Monument deeply split the people of Tulare County. The county’s board of supervisors even filed suit to overturn the monument, a case that ultimately failed. Others, who valued the groves for their inspirational beauty, celebrated the new direction as long overdue.

Many years after the creation of the monument, some local residents still argue about whether it represents the right direction for the management of more than a quarter of the Sequoia National Forest. What emerges from this debate with great clarity, however, no matter which side of the argument one supports, is the great power that the giant sequoia trees and the forests in which they grow exercise over us all.

Truly, we care about these trees and their future.

March, 2014

v>

“This Nation’s Giant Sequoia groves are legacies that deserve special attention and protection for future generations. It is my hope that these natural gifts will continue to provide aesthetic value and inspiration for our children, grandchildren, and generations yet to come.” — President George H. W. Bush

“Ancestors of Giant Sequoia trees have existed on Earth for more than 20 million years. Naturally occurring old-growth Giant Sequoia groves located in the Sequoia, Sierra, and Tahoe National Forests in California are unique national treasures that are being managed for biodiversity, perpetuation of the species, public inspiration, and spiritual, aesthetic, recreational, ecological, and scientific value.” — President George H.W. Bush

“Sequoias are distributed in a small number of isolated concentrations, traditionally called ‘groves’ in a narrow strip less than twenty miles wide on the west slope of the Sierra Nevada. . . . Sequoias naturally occur on an infinitesimal fraction of the earth’s forested surface…The global rarity of old growth sequoia forest cannot be overstated.”– Dwight Willard

“Two local women, Charlene Little and Carla Cloer, stumbled onto … a logged-out Giant Sequoia forest in 1986, in what they had believed were protected groves. The environmental organizations they alerted mediated for a year and a half with the Forest Service, cattlemen, millowners, and recreationists involved. . . . This logging controversy of the late 1980s was a surprise throwback to the days a century earlier, before national and state parks existed, when Giant Sequoias were heavily logged in the the southern Sierra.” — Verna R. Johnston

“. . . for over 100 years, beginning with the residents of Visalia, California, Americans have sought to save these giant sequoias. . . . We’re doing our part today to make sure that the monarchs will be here after we’re long gone, rooted strong in the web of nature that sustains us all.” — President William J. Clinton

“The giant sequoia groves in Sequoia National Forest are now protected from commercial logging by the new Giant Sequoia National Monument. . . . Future management of these groves . . . is still largely dependent upon the administrative planning processes of the U.S. National Forest Service. . . . an interested and informed public is still essential to their preservation and restoration over the long term.” — Dwight Willard

Directions:

Giant Sequoia National Monument,

Coordinates 36.0400° N, 118.5044° W

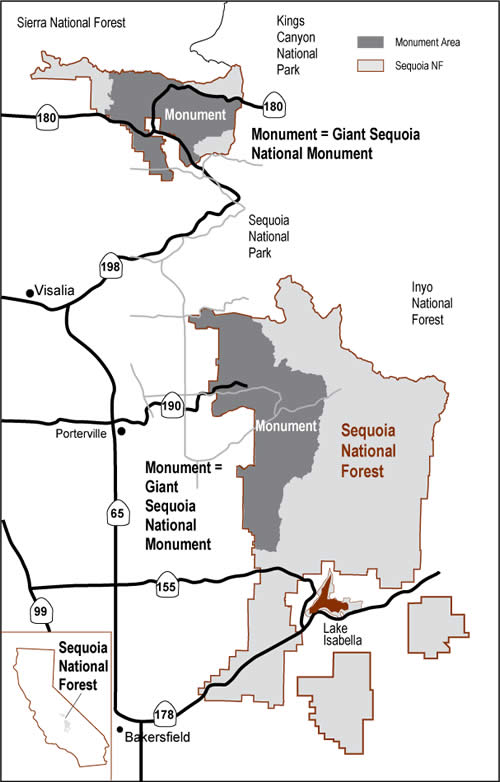

The Monument is most easily accessible via three main highways (198, 180, and 190).

Northern Portion:

From Visalia, take either Hwy 198 east into the National Park and continue north on the Generals Highway to the Monument, or take Hwy 63 north to Hwy 180 east into the Monument.

Southern Portion:

From Porterville, take Hwy 190 east into the Monument.

Note: The monument is in two sections. The northern section surrounds General Grant Grove and borders other parts of Kings Canyon National Park and Sequoia National Park. It is administered by the Hume Lake Ranger District.

The southern section, administered by the Western Divide Ranger District, includes Long Meadow Grove, and borders the south boundary of Sequoia National Park and the eastern portion of the Tule River Indian Reservation.

Detailed directions, maps, and additional information can be found at this link: The Giant Sequoia National Monument.