Perhaps the most remote and least known of all the major geographical features of Tulare County is to be found in the county’s southeastern quadrant. Here, near the southern end of the Sierra Nevada, the range takes on a distinctive character found nowhere else. Instead of raising high peaks against the sky, this part of the Sierra takes the form of an extensive uplifted plateau. Those who know the Sierra call this region the Kern Plateau. No other part of the Sierra Nevada looks anything like it.

A combination of altitude and aridity makes this part of the Sierra unique. Much of the undulating surface of the plateau lies between 7,000 and 9,000 feet. Usually, altitudes of this height would guarantee generous winter snowfall, but the Kern Plateau finds itself within the rain shadow of the Great Western Divide, the north-south ridge that forms the headwaters of the Kaweah and Tule rivers. To the east of the divide, exhausted winter storms deposit only a fraction of the water they dump on the mountains immediately to the west. No other part of the High Sierra is so dry.

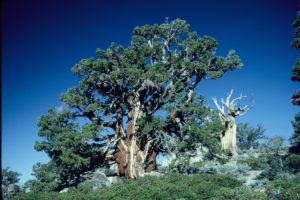

Those who have visited the Kern Plateau know how all this comes together. Open sandy meadows, covered with sparse grass and sagebrush, run for miles. Around them, rolling hills support open stands of Jeffrey, lodgepole, and foxtail pines. Small streams flow across the sandy landscape, and it is here that the golden trout – California’s state fish – evolved. The bright colors of the golden trout mimic the shining flakes of mica and quartz in the stream bottoms.

Getting to the Kern Plateau country has always been difficult. Travelers coming from the San Joaquin Valley must surmount the Great Western Divide, then cross the rugged and deep canyon of the main stem of the Kern River before they can climb onto the plateau. To the east, a row of peaks — including 12,700-foot Olancha Peak, and a mile-high escarpment separate the plateau from the northwestern edge of the Mojave Desert near Ridgecrest.

The history of the plateau reflects its remoteness. Like all the surrounding mountain country, the Kern Plateau was first set aside as public land when the Sierra Forest Reserve came into being in 1893. In 1908, when the reserve lands were re-designated as national forests, the Forest Service divided the plateau between the Sequoia and Inyo national forests, a condition that continues today.

For the first half of the twentieth century, the Forest Service essentially left the plateau alone. Cattle ranchers’ herds grazed the meadows each summer, and hunters and fishermen packed in to enjoy the solitude. Most of these visitors arrived on horseback. Over time, the secluded country earned a small cadre of dedicated fans, people who enjoyed the quiet and beauty of this often-stark high country retreat.

Foremost among these were Ardis Walker and his wife, Gayle Mendelssohn Walker, who grew up in Tulare County. By the early 1950s, Ardis and Gayle lived in Kernville, the southern entrance to the Kern Plateau region. There, they owned and operated the Kernville Inn. The two pursued many interests. They worked hard to establish CSU Bakersfield, and Ardis wrote poetry. The High Sierra, however, always stayed near the top of their personal lists. Year after year, they traveled into the mountains and especially into the Kern Plateau country.

As early as the 1930s, Walker had begun to worry that the beauty of this wilderness retreat might eventually be compromised by road building and logging. In 1947, he persuaded a high-ranking Forest Service official, Regional Forester Pat Thompson, to accompany him on a prolonged trip through the heart of the Kern Plateau. Thompson was so impressed that he issued an order reserving the country for wilderness recreation.

A decade later, however, at the height of the economic boom of the 1950s, the Forest Service reversed itself and announced that it would allow the plateau to be logged. By the early 1960s, roads were being pushed into the plateau from both east and west, and truckloads of logs were spilling out of the region.

Ardis Walker was appalled. Now in his 60s, he recruited a new generation of activists to help him protect the landscapes he so appreciated. Schoolteacher Bob Barnes of Porterville played an important role, as did Joe Fontaine, who lived in Tehachapi. The campaign to preserve at least a portion of the plateau as wilderness went on for a full twenty years, until finally, in 1978, Congress gave protection to the northern portion of the Kern Plateau, designating more than 300,000 acres as the Golden Trout Wilderness, about 80% of it in Tulare County.

The wilderness also included much of the rugged eastern slope of the Great Western Divide, as well as a major portion of the canyon of the Kern River. Ardis Walker celebrated the wilderness he had worked so hard to create and lived another dozen years before he passed away in 1991 at the age of 90.

Today, the Golden Trout Wilderness protects the High Sierra country immediately to the south of Sequoia National Park. Within this Forest Service-administered wilderness, life goes on much as it has for more than a century. Cattle graze the meadows during the summer months, hikers, hunters, and fishermen come to enjoy the solitude, and the beauty of the land remains for all to enjoy.

December, 2014

“I’ve never found an area I like as much as the Sierra. The granite, the light, the high elevation, the good weather, the open aspect of views — I haven’t seen that combination anywhere else. To many people, . . . the Sierra has a mystique . . . If they’ve seen it, they know it’s worth saving.” — Ardis Walker

“You could see the forest cut and not growing back, and I realized that too much would be gone if we didn’t do something about it. . . . It was a long battle, and it often seemed that we had lost. I worked on that for forty years, but other people carried [it] out. Thank God we have people like Bob Barnes and Joe Fontaine.” — Ardis Walker

“The plateau of the golden trout with its little streams, grassy meadows, and tiny boiling canyons should be preserved forever and its great old trees kept as cathedrals of the spirit. To do otherwise is to disregard its real value. The region has a vital role to play, one involved with intangible values and dreams of mankind. Here is part of America as it used to be.” — Ardis Walker

“. . . the Congress finds and declares that it is in the national interest that . . . these endangered areas be promptly designated as wilderness . . . to preserve . . . as an enduring resource . . . managed to promote and perpetuate the wilderness character of the land and its specific multiple values for watershed preservation, wildlife habitat protection, scenic and historic preservation, scientific research and educational use, primitive recreation, solitude, physical and mental challenge, and inspiration for the benefit of all of the American people of present and future generations . . . .” — Endangered American Wilderness Act of 1978

“As we topped the pass, we looked to the north over a sweep of scraggly, wind-tortured pine and fir . . . . Far beyond was Mt. Whitney, brooding as always over the plateau. Unchanged from when the mountain men came through, this is still a land of silences, ancient trees, and far vistas.” — Sigurd F. Olson

NOTE: The GTW is far too large for a useful map of it to appear on this page. USDA’s Forest Service map of Sequoia National Forest is a good aid for trip planning, and the Forest Service suggests the Golden Trout Wilderness map by Tom Harrison.

The GTW can be accessed from Tulare County via Sequoia National Park (Mineral King) on the north, and via Mountain Home Demonstration State Forest on the west. Trails for hikers and horses can be accessed from Hwy 190 (east of Porterville) near Quaking Aspen via Forest Service Road 21S50, which leads to Summit, Clicks, and Lewis Camp trailheads; Lloyd Meadow Road (Road 22S82), which leads to Jerkey and Forks of the Kern trailheads; and Balch Park Road to Mountain Home Demonstration State Forest, Shake Camp trailhead. From the south, access is via Sherman Pass Road via Nine Mile Road to Blackrock trailhead, north of the Black Rock Ranger Station, to hike down to Casa Vieja Meadow. (Horseshoe Meadow above Lone Pine is the best roadhead from the east, in Inyo County.) NOTE: These roads are closed in winter. Many of the Forest Service roads are dirt.

Scenic drives offering views of the GTW: Western Divide Highway (M107) travels 15 miles of the dramatic ridgeline that divides the Kern River watershed from the Tule River watershed, beginning at Quaking Aspen Campground and ending at the junction with M50 (take Hwy 190 east from Porterville to connect with M107 at Quaking Aspen; you can also go south from Porterville on Hwy 65 to Ducor, where you will take J22 east through Fountain Springs to California Hot Springs and Road M50 north). The Sherman Pass Road (22S05) provides access to the Kern Plateau, and a view of Mt. Whitney from Sherman Pass from the south end of the Western Divide Hwy; go east on M50 and M99 past Johnsondale and onto 22S05 over the pass. NOTE: These roads are closed in winter and are often steep, narrow, and winding; check conditions before driving.