Nature rules again at Dry Creek Preserve.

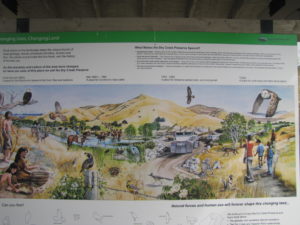

Situated on 152 acres of a former gravel quarry on a mostly dry stream bed north of Lemon Cove, Dry Creek is ecologically significant as a sycamore alluvial woodland. It is one of only seventeen such environments scattered through Central California and one of the largest. It was home to a thriving settlement of the Wukchumne tribe in pre-European-American times. Then it was used for cattle grazing. More recently, it was a rock and gravel mine for twelve years until that use was nearly exhausted by the end of the twentieth century.

Dry Creek was restored to its natural – although not original – condition by a partnership led by Sequoia Riverlands Trust (SRT). It is the first such mining reclamation site in Tulare County and is singular because the restoration effort used the damage caused by the mining operations to create unique and enhanced habitat.

Hilary Dustin, conservation director of Sequoia Riverlands Trust, worked on the restoration from its beginning in 2004. The first time she saw Dry Creek, it was so desolate and gloomy it reminded her of Mordor in “Lord of the Rings.”

“This mine had affected virtually every square foot of the property,” Dustin said in an extensive video interview with Tulare County Treasures. “You would think, this is devastation, you know, it’s ruined; we can never do anything with it.”

The multi-year mining operation at Dry Creek had never been popular with the neighbors. When the owner, Artesia Mining Company, eventually foundered, one of its creditors, California Portland Cement, took over the property and was considering what to do with it. One of the neighbors urged Sequoia Riverlands Trust to talk with the new owner. The land trust contacted the cement company and initiated a meeting.

No longer viable as a mine, the property was subject to expensive reclamation work mandated by the state of California. After only weeks of deliberation, California Portland Cement decided to turn the property over to SRT. Both sides had seen an opportunity: California Portland Cement shed its obligation to clean up the mine site, and SRT saw a chance to restore a unique natural habitat. That was in 2004, and it began more than eight years of restoration to return Dry Creek to something resembling its natural state.

Shortly after acquiring the property, SRT received a $200,000 grant from a private foundation to begin planning and restoration. That same year, the trust added another $100,000 from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, a federal agency, to pay for the reclamation. More assistance arrived in short order: The Nature Conservancy offered its services and connected SRT with experts at University of California, Berkeley and UC, Davis.

Landscape students from California State Polytechnic University, Pomona supported the project. Kaweah Delta Water Conservation District extended its expertise. Two grants from the state of California helped pay for visitor amenities such as signs and restrooms. Volunteers showed up to help move rocks, clear trails, and plant trees.

Dustin estimates that about $1.2 million in donations contributed to the Dry Creek Preserve restoration, and of that about a half million dollars was from in-kind donations of professional and volunteer work.

“The vision for the reclamation was not just to get back to the way things were before mining,” Dustin said, “which was essentially open grazing land, but to actually do what we could to enhance the values out there for wildlife habitat and also for people to come and enjoy the place and to make it a wonderful outdoor classroom as well.”

The restoration created opportunities to improve upon what nature had created. In some cases, the restoration project removed berms and ditches so that the water returned to its natural courses. Mining had also disrupted the water table, and some deep quarries created pools, including a small lake that wasn’t there before. With the natural habitat restored, oaks and sycamores began to return. Bird and animal species took hold in the newly restored environment.

“There’s a lot of volunteer cottonwoods, willows, and other vegetation that came back on its own, once mining stopped,” Dustin said. “But we’re kind of nudging it along, trying to help the sycamore alluvial woodland come back a little faster than it might otherwise.”

It’s a case of nature getting by with a little help from its friends.

“We actually have more native plants out there now than we did before and we have a more natural stream flow,” Dustin said.

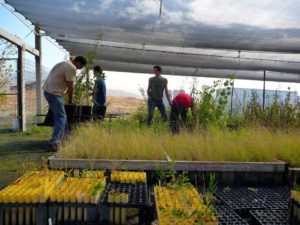

Dry Creek was also established as a kind of open-air laboratory, with nature as the scientist in charge. SRT envisions it is as a place for field study and natural experiments. The trust has already established a native plant nursery and a native plant demonstration garden.

The preserve welcomes what Dustin calls “citizen scientists”: visitors who make observations about habitat or wildlife and record them. It also encourages students to use the site as a classroom.

Dry Creek has been a tribal village site, a cattle grazing site, a unique natural habitat, and a mine. Now a reclaimed site, it still shows evidence of all those uses in its past. And all of them have something to teach people.

“Many people would have considered this place trashed, if they had gone out to Dry Creek ten years ago,” Dustin said in 2014. “If they go out there today, I think they would say, Wow, look what happened when we sort of got back out of the way of nature, and we helped a little bit to do some restoration.”

July, 2014

It is connected by a common root ball. Rarely exposed, some root balls measure 15 feet in diameter and have been pushing new stems for centuries. Some stems here are three to four hundred years old—alive, perhaps when Sir Francis Drake claimed California for Spain. Imagine how old the root balls must be!” — John Dofflemyer

“We started a native plant nursery at Dry Creek. And we got to thinking. We’ve got restoration going on at Kaweah Oaks Preserve, at the Herbert Preserve, why don’t we start growing more things? And then NRCS, which works with other land owners doing restoration projects, asked if we would raise plants for them. So now we are providing tens of thousands of plants to these other projects.” Hilary Dustin

“Now we’re really shifting our focus to ways that people can continue to be involved out there, whether it’s in a formal learning setting, like school tours for kids, or a service learning project, helping kids meet their community service hours, but also getting them outdoors and learning the story of our area and how they can become involved in conservation, in caring for the land.” — Hilary Dustin

Directions:

Address: Dry Creek Preserve, 35220 Dry Creek Drive, Woodlake, CA 93286

GPS Coordinates: 36.43188, -119.02469300000001

From Visalia, take Hwy 198 east to Lemon Cove. Turn left onto Hwy 216 toward Woodlake. Cross the bridge in 1/2 mile and turn right onto Dry Creek Drive. The Preserve is 2 miles north, on the right.