Two elusive plants and the love for flowers of a rancher/naturalist were the factors in a formula that conserved 110 acres of Lewis Hill as a nature preserve in the Sierra Nevada foothills of Tulare County. Cole Hawkins is the rancher, and his family once owned 600 acres of Lewis Hill. From his childhood fascination with plants, through his developing interest in conservation and persistence in preserving a site he loved, Hawkins worked with many others to protect what he saw as miracles of nature.

Set in rocky foothills north of Porterville, Lewis Hill is an unprepossessing, grassy hump that rises to 1,028 feet in the middle of grazing country. Arid and speckled with random outcroppings of rock, it is typical of foothills grassland and blue oak habitat, although treeless. Each spring the hill supports an enticing mix of wildflowers: California poppy, wild hyacinth, miner’s lettuce, blue dicks, fiddleneck, popcorn flower, milk thistle, and cluster lily among them.

Two flowers are imperiled: the San Joaquin adobe sunburst (Pseudobahia peirsonii, classified as endangered) and the striped adobe lily (Fritillaria striata, classified as threatened). The common names of both plants indicate they grow only in rocky, clay-based soil called adobe, Lewis Hill is one of the few places on Earth with the appropriate soil and climate for these species to thrive. They flower on Lewis Hill briefly from mid-January into early spring, and disappear the rest of the year. In this ephemeral botanical environment, Cole Hawkins fell in love.

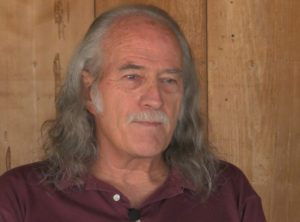

“I‘ve always had a real interest in plants and animals,” Hawkins said. “I think I was born with it. I was just amazed by plants.” Hawkins grew up in citrus orchards in Southern California. His family bought the Beatty Ranch, which included much of Lewis Hill in Tulare County, in 1953, when Cole was three years old. His father named it Hermosa Tierra, “Beautiful Land.” They grew citrus and olives and ranged cattle on about 600 acres bisected by Plano Road and rising from the base to the peak of Lewis Hill.

From spending his early years there off and on, Hawkins became enchanted with the place. At first he was more taken with the animals than the plants – bobcats, coyotes, squirrels, the occasional mountain lion, deer, fox, and striped and spotted skunks. But gradually he started noticing the plants, too, especially the bright indigo cluster lilies. “One of my milestones of the year was when the first brodiaea would bloom,” he said. “And brodiaea is a beautiful small blue lily. I was always excited when that happened.”

Hawkins started working on the ranch in 1969, but took time off to pursue his college degree. Although he enjoyed the natural wonders of the property, the purpose of the farm was to raise food. The focus on the ranch was to suppress plants that weren’t citrus and olives, Hawkins said. “My uncle was afraid they were competing with the trees for water and nutrients.”

They knew that grazing cattle on the ranch would suppress the wild oats, an introduced species that competed with the native plants. Hawkins said his interest in managing the land and encouraging the native plants started with his experiments in selective grazing. And that led to the conservation of Lewis Hill.

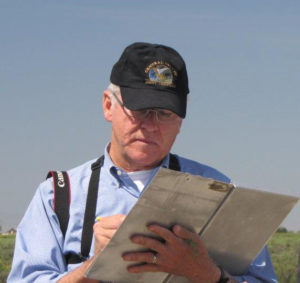

Hawkins worked toward a Master’s degree in biology at California State University, Fresno while he nurtured his interests in botany. He would roam the fields of Lewis Hill, armed with a Munz guide to California plants, cataloging the various species he found.

He decided he needed to learn more about what was on his ranch, so he asked for help from biologist Dave Chesmore and botanist Howard Latimer at Fresno State. He conferred with Bob Barnes of the Tulare County Audubon Society and biologist Rob Hansen. He called on another local farmer, Jack Zaninovich, who was active in the California Native Plant Society. They eventually determined that Lewis Hill had two threatened or endangered species, the striped adobe lily and the San Joaquin adobe sunburst.

Hawkins began managing the ranch when his uncle retired in 1978. A few years later, he met a self-described “city girl,” a musician from Detroit named Priscilla Haapa. Priscilla moved to Porterville in 1972, where her daughter, Shanda Lowery, was born. Priscilla played principal cello in the Tulare County Symphony, taught private cello students, and started the string instrument program in the Porterville schools in 1973. She met Cole Hawkins at an Audubon Society meeting in 1981. He was looking for a volunteer for his water conservation booth at the Porterville Fair.

“I was the only one who signed up for helping him at this booth,” Priscilla said. “So that was the start of us realizing how much we really had in common. “About six months after that, I was going to leave Porterville, because I thought, ‘Oh, this is just too small of a town and all that.’ But by then I had already realized that Cole and I had something very special going.” Cole and Priscilla married in 1982. Two years later they moved into a house they built on Lewis Hill on 25 acres of ranch property the Hawkins family gave them.

They both knew they wanted to keep Lewis Hill just as it was. They reveled in their views of wildlife, sweeping vistas, and delicate flowers. The fact that some were threatened or endangered was an asset. They would share strategies to preserve the place, talk to dozens of other people, and explore their options. Family events forced their hand.

Hawkins’ mother, who owned a majority of the ranch, died in 1989, and the Hawkins family made plans to sell the property. Cole Hawkins was eager to pursue a Ph.D. in wildlife and fisheries science, and Priscilla wanted a place where she would play her cello and teach. They moved to Davis in 1991.

Meanwhile, they continued their plans to preserve some of Lewis Hill. His brothers and sister donated 90 acres to the project, and Hawkins donated 20 of his 25 acres. Cole gives Priscilla the credit for coming up with the idea of a conservation easement for the property. They approached various organizations that could take the land in trust. For a time, the Nature Conservancy was interested, but the project eventually wasn’t big enough for them.

Finally, in 1994, the family donated 110 acres to the Kern River Research Center, which Bob Barnes had helped to establish. Six years later, Lewis Hill was acquired by the Tule Oaks Land Trust, which has become part of the Sequoia Riverlands Trust (SRT). Each spring, SRT conducts a guided wildflower walk on Lewis Hill. Other times the property is open to groups for study and research only by arrangement with SRT.

Cole and Priscilla Hawkins still return to visit Lewis Hill and Hermosa Tierra. The farmer who bought the ranch has kept it in citrus production, allaying the Hawkines’ fears that the property would be developed. “We just loved Lewis Hill and we wanted to keep it for other people to be able to enjoy it the way that we did.”

Lewis Hill remains a preserve for the unique natural habitat of the Southern San Joaquin Valley and Sierra Nevada foothills, just the way Cole and Priscillla Hawkins wanted it to be.

February, 2016

“Here there are two very rare flowers including the striped adobe lily (Fritillaria striata). This flower only grows on a few scattered hills in the area and nowhere else on earth. Why? Because it prefers a certain type of soil that comes from a certain type of rock. [T]he Sierra Nevada . . . in its central and southern portions is mostly granite. . . Lewis Hill is made instead of a mix of dark volcanic and metamorphic rocks. And wherever this rare rock type occurs in this part of the world you may find this rare lily growing on it in late February and early March.” — Tarol

“Fritillaria striata produces an erect stem 25 to 40 centimeters tall and bearing pairs of long oval-shaped leaves 6 to 7 centimeters long. The nodding flower is a bell-shaped fragrant bloom with six light pink petals each striped with darker pink. The tips roll back. In the darker center of the flower is a greenish-yellow nectary surrounded by yellow anthers.” — iNaturalist.org

“I can show you how beautiful the lilies are by showing you a photograph, but oh how I wish I could let you get a whiff of them! They smell heavenly! They are closely related to the leopard lilies that grow higher in the mountains and like them exhibit one of the best wildflower smells that I have ever smelled. So be sure if you ever get a chance to meet this flower to get on your hands and knees and smell them, too.” — Tarol

“The main threat to the [striped adobe lily] plant is cattle grazing, wild pigs, and invasive species of grasses. Fritillaria striata is listed by the State of California as a Threatened species, and is on the California Native Plant Society Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants of California, listed as Seriously Endangered in California.” — iNaturalist.org

“San Joaquin adobe sunburst is a member of the Asteraceae family. It is an erect annual herb about 1 to 6 decimeters (4-18 in.) tall, loosely covered with white, wooly hairs. Its alternate leaves are twice divided into smaller divisions (bipinnatifid), triangular in outline, and 2 to 6 centimeters (1 to 3 in.) long. Flower heads, which appear in March or April, are solitary at the ends of the branches. The ray flowers are bright yellow and equal in number to the subfloral bracts. They are about 3 millimeters (0.1 in.) long with many disk flowers. The dry fruits, called achenes, are black.” — U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

“Conversion of natural habitat to residential development is the primary threat to San Joaquin adobe sunburst. In addition, road maintenance projects, recreational activities, competition from nonnative plants, agricultural land development, incompatible grazing practices, a flood control project, transmission line maintenance and other human impacts also may threaten the species.” — U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Directions:

Note: Usually open only one day per year, as scheduled by Sequoia Riverlands Trust. Please do not visit the Preserve without express permission from SRT and do not trespass on the private land surrounding the Preserve.

From Visalia, take Hwy 198 east to Hwy 65 south toward Porterville. Exit onto Henderson going east toward Plano Road. Take Plano Road south to the crest of the first hill. Lewis Hill is on the west side of the road.

(Alternatively, continue south on Hwy 65 and exit east on Hwy 190 into Porterville. Exit Hwy 190 north onto Plano Road, about one-and-a-half miles east of Highway 65. Drive north on Plano Road about four miles to the crest of the first hill. Lewis Hill is on the west side of the road.)