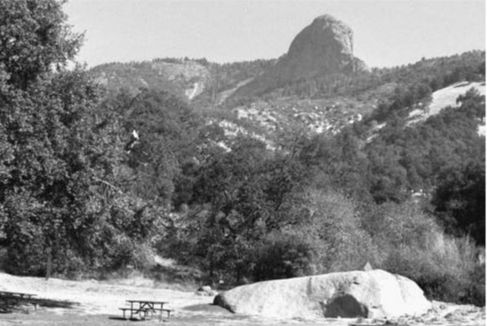

We tend to divide the Treasures of Tulare County into two categories – natural and cultural – but in one special place the two are blended together in a nearly seamless fashion. That place is Moro Rock in Sequoia National Park.

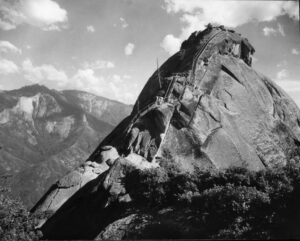

A towering granite dome, Moro Rock stands on the southern edge of the Giant Forest plateau, home of the world’s largest trees. The rock’s summit offers one of the great views of the southern Sierra. The 360-degree panorama takes in everything from 13,000-foot peaks to the floor of the San Joaquin Valley. The dome also overlooks the huge canyon of the Middle Fork of the Kaweah River, which cuts into the Sierra’s western slope by nearly a vertical mile, a scale that makes it equal in depth to the Grand Canyon of Arizona.

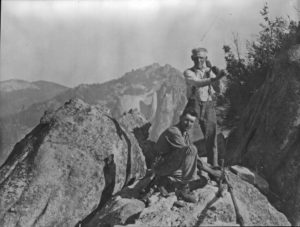

Because of both its prominence and the great views from its 6,720-foot peak, Moro Rock has long attracted visitors who seek out its summit. The rock was first climbed by pioneer cattleman Hale Tharp and his family in the 1860s, and they found getting to the top a difficult scramble. The only possible route led along a narrow fin of granite with alarming exposure on both sides. A false step could result in a fall of several hundred feet.

After the Giant Forest, with its wonderful sequoia trees, became a part of Sequoia National Park in 1890, the rock gained attention as a tourist destination. By 1903 the soldiers who looked after the park in those early days had built a wagon road that allowed visitors to get to the northern base of the rock. Ascending the rock, however, still required a risky scramble.

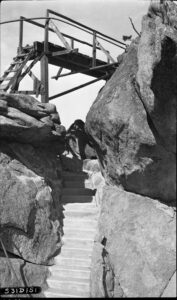

Finally, in 1917, the park found the money to do something about Moro Rock. During that summer a set of wooden steps was built up the narrow ridge that led to the summit. The steps made it easier to get to the top of the rock, but even after they were constructed few called the climb easy. Climbing Moro Rock still required a vertical ascent of over 300 feet – equal to a thirty-story building – and many found the steps almost as exposed and alarming as the rock itself. Jumping from boulder to boulder, the wooden steps leapt across great gaps of open air, and much of the route had only minimal handrails. Nonetheless, the rock became one of the park’s major attractions.

The Giant Forest area receives heavy snow during the winter months, and the wooden steps soon proved to be both fragile and expensive to repair. A better solution was needed.

By the late 1920s, the National Park Service, the agency now in charge of Sequoia National Park, had begun to develop both a design philosophy and professional staff to execute its concepts. The design philosophy, called “rustic architecture,” called for buildings, bridges, and even trail structures to blend into the landscape as completely as possible. The key to this was the use of natural materials. Also important was how structures were placed on the ground; whenever possible, they needed to be nestled into the natural shape of the terrain.

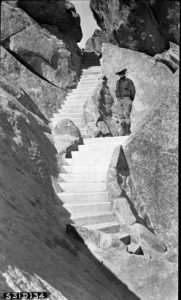

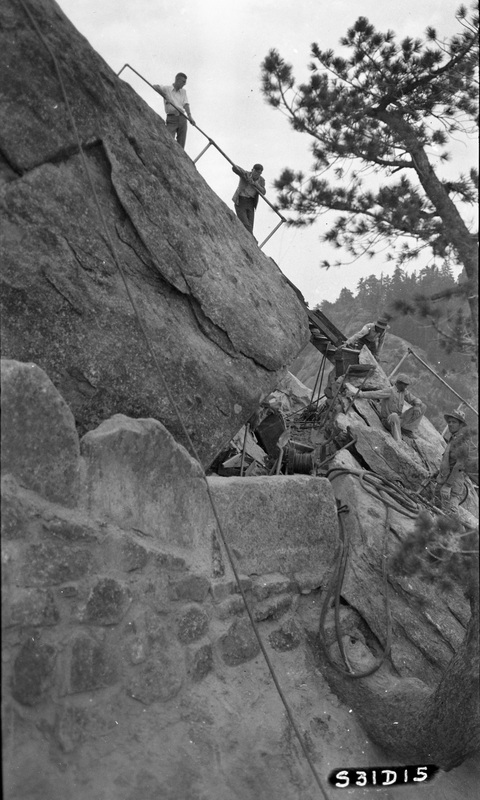

Moro Rock presented a severe design challenge. The rock badly needed safe, permanent steps, but how could such a route be placed upon the towering granite promontory without disfiguring it? To answer the question, the Park Service assigned two men the challenge of designing a permanent trail to the summit of Moro Rock: engineer Frank Diehl and landscape architect Merel Sager. The two men studied the rock carefully, and eventually worked out a brilliant solution. The new trail, instead of running straight up the north ridge, would seek out the rock’s natural ledges and fissures. By linking these natural routes, a circuitous route to the summit could be constructed. To blend the new trail into the rock, it would be framed by granite masonry walls built of large boulders taken from the site. Even the trail’s surface, to be made of concrete, would be colored so as to look like granite.

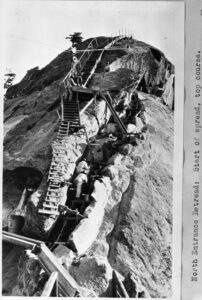

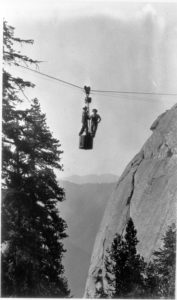

Construction took place over the summer of 1931. To allow the construction crew to move large rocks and concrete along the trail’s proposed route, the Park Service erected a “high line” above the project site that allowed materials to be moved through the air and then dropped into place. To establish the highline, the government borrowed a life saving cannon from the Coast Guard, a device used to shoot ropes across water to wrecked ships stranded on rocks or sandbars. By the end of the summer, the new steps were complete, and for the first time casual visitors could access Moro Rock’s summit. The climb still involved the ascent of nearly 400 steps, but compared to the old wooden steps, the route now offered a much greater sense of physical security. More amazingly, when viewed from a distance, the trail blended so well into the rock that it essentially disappeared. Diehl and Sager had conquered Moro Rock without defacing it.

Today, more than eighty years later, Moro Rock remains one of the best-loved features of Sequoia National Park. Several hundred thousand visitors climb the rock each year, all of them following the trail built so carefully in 1931. The route remains unchanged and nearly all of the massive granite walls erected so long ago still stand. Modern safety concerns have seen the addition of metal handrails to some of the stonework, but essentially the trail functions, and still appears, as originally designed.

Over the years, appreciation of the trail’s design has grown. It is hard to imagine how the trail could have been more carefully placed on the rock. In 1978, in recognition of its superlative design, the Moro Rock Stairway was added to the National Register of Historic Places as an example of rustic design by the National Park Service. The National Register nomination form lauds both the design of the trail and the quality of the workmanship that built it.

At Moro Rock, nature and human design come together to form yet another of Tulare County’s Treasures.

May, 2013

“This stairway was built [in 1917] to afford the best possible opportunity to view the magnificent scenery of the park region and the mountains beyond. Moro Rock, 6,719 feet in altitude, is a monolith of enormous yet graceful proportions. Its summit is nearly 4,000 feet above the floor of the valley of the Middle Fork of the Kaweah below, and the huge granite mass stands apart from the canyon wall in a manner that affords one a marvelous panoramic view.”—Stephen Mather

“At Sequoia . . a new stairway was built [in 1917] to the summit of Moro Rock, from which the entire park and surrounding mountains could be viewed. The sturdy 364-foot stairway of wood timbers, planks, and railings was a common type of trail improvement built in the 1910s and 1920s to provide safe access to precipitous and spectacular viewpoints, often across steep and rugged ground.” —Linda Flint McClelland

“To [Stephen] Mather [creator of the National Park Service] the stairway was magnificent, a fine achievement for service engineers and a demonstration of the fledgling agency’s commitment to making park scenery accessible to the general public and not just seasoned mountaineers.” —Linda Flint McClelland

Directions:

Address: In Giant Forest, Sequoia National Park

Latitude/Longitude:

36-32’39” N, 118-45’54” W

36.5441116, -118.765098

From Visalia, take Hwy 198 east through Three Rivers into Sequoia National Park (entrance fee). As you enter the Giant Forest Village area, follow the signs and turn right onto the road to Crescent Meadow and Moro Rock parking lot (road closed to vehicle traffic in winter; RVs and trailers not recommended; shuttle service available in summer).