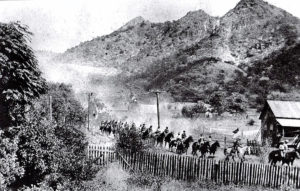

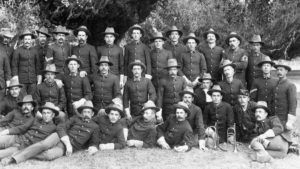

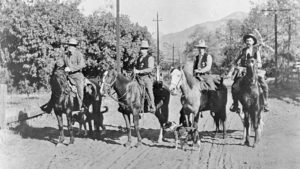

In the summer of 1906, Sequoia and General Grant national parks were still being administered by the United States War Department (now known as the Department of Defense). That summer, Captain Kirby Walker was serving as these parks’ Acting Superintendent. In May, he led Troop F of the Fourteenth Cavalry and a detachment of the U.S. Army Hospital Corps (the latter detailed to work on sanitation issues in the increasingly-visited parks) on the 260 mile march from the Presidio of Monterey to establish their camp on the North Fork of the Kaweah River near the little town of Three Rivers.

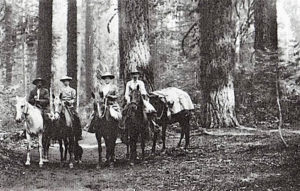

Four local civilian rangers were also employed by the government to work with the troops. Their principal duties were “the preservation and protection against injury of the flora, trees, animals, birds, fishes, and wonders of nature on the Government lands within the parks, and the carrying out of such rules and regulations as the Interior Department might see fit to issue.” They were also “to prevent the unauthorized use of Government lands within the parks by cattle and sheep men, [and] to prevent forest fires.”

The troops were on site only in the summer, usually from early June to mid-October or earlier, depending on the weather. The civilian rangers were responsible for patrolling and working on park projects year-round.

That summer of 1906, Captain Walker decided that more ranger cabins were needed, to “serve as shelter during inclement weather for the rangers and detachments of soldiers, as a storage place for provisions, forage, and tools, and as a central point from which to patrol.” Two cabins had already been constructed on the Giant Forest road, another was underway at Hockett Meadow. Walker wanted to add four more in 1907: in the Black Oak area (in Sequoia’s northwest quadrant ), and at Giant Forest, Clough Cave, and Quinn’s Horse Camp.

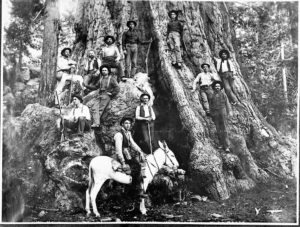

Growing numbers of tourists were visiting the park, and they needed access to its attractions. Thus, the Tar Gap, South Fork, and Quinn’s Horse Camp trails were being repaired in 1906. At over 8300 feet in elevation, Quinn’s Camp provided cool weather for visitors coming to the mountains for weeks or even months to escape the Valley’s long summer heat. It was a good camping area, with fine fishing nearby and a large meadow offering plentiful forage for stock. The popular soda springs only a mile away were another attraction. From their water, said to rival the famous Apollinaris water of Germany, visitors could make sparkling lemonade for further summer refreshment.

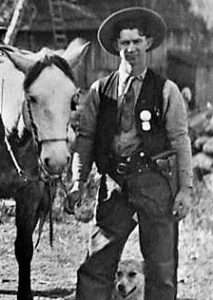

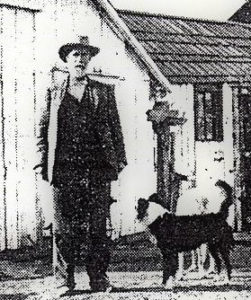

On July 23, 1906, when a new slot opened in the park’s ranger force, Superintendent Walker appointed Harry F. Britten to the post and assigned him to duty in the southern part of Sequoia. Britten had originally been hired as a park ranger in 1902, but while on patrol in March, 1903, he accidentally discharged his pistol into his right thigh, resulting in $1,000 worth of medical expenses, amputation of his right leg above the knee, and eventually being fitted with an artificial leg.

A year after the accident, Britten had learned to walk on the new limb and was employed as a clerk in the Sequoia Forest Reserve (predecessor of Sequoia National Forest). He had received no government compensation for his on-duty injury and consequent expenses, so Captain Walker thought it only fair that Britten should be rehired by the park.

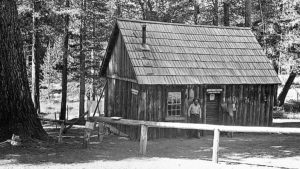

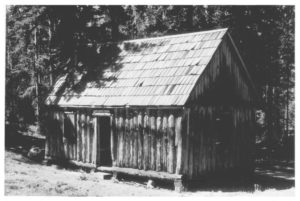

Thus, Harry Britten became responsible in 1907 for building the Quinn Ranger Station. Located on the southeast corner of the Quinn Horse Camp Meadow in a dense pine and fir forest, the one-room log cabin measured nineteen feet long by thirteen feet wide. Each long wall featured a central door and a glazed window while the end walls were solid. Split logs, rounded side out, placed (unusually) vertically, formed the walls, and, laid horizontally, formed the floor. Each vertical log wall stood on a big horizontal log providing a sill that was supported on a foundation of granite and wooden blocks. Shakes attached to a wooden frame created the gable roof.

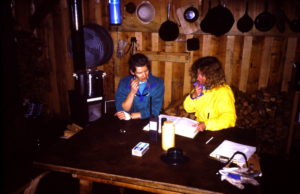

The simple cabin had no interior paneling or ceiling, but it was equipped with a wood stove and shutters for the windows, and an outhouse stood nearby. Within a few years, a barn was added about 75 feet away, along with a rail fence enclosing a few acres of meadow for horse pasture.

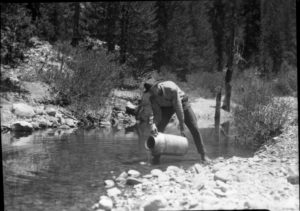

Captain Walker was pleased. His 1907 report praised the park rangers’ work. Captain Walker noted that “In addition to their ordinary duties they have been of great assistance this year in taking immediate charge of the construction of ranger cabins, trail work, telephone work, and the distribution of fish. There are ranger cabins now at Rocky Gulch, Colony Mill, Hockett Meadows, and Quinn’s Horse Camp.”

He also wrote that “A first-class trail connecting Hockett Meadows and Quinn’s Horse Camp was built this year, an important addition to the trails in use,” and reported that about 1100 tourists and campers visited General Grant Park during the 1907 season and about 900 visited Sequoia Park, up from around 900 and 700 respectively in 1906.

Rangers used the Quinn cabin for a number of years as a headquarters for patrolling the southern part of the park. In 1917, the newly-created National Park Service took over administration of the parks, and its rangers continued that use until sometime after 1940. Then, downgraded to a patrol cabin, Quinn continued to serve park rangers, trail crews, and pack trains in the warmer months, and snow surveyors in the winter.

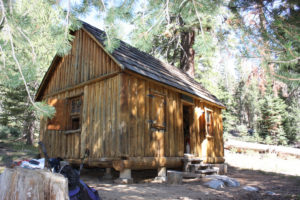

Over the many decades since Quinn was built in 1907, park craftsmen have worked to maintain, improve, and restore this iconic ranger station. The addition of windows, one in each end wall, and another in each long wall, brought in more light. Sometime in the 1950s or 1960s, the rustic cabin was renovated. Its foundation was improved, and new sills were placed under the walls. The doors and shutters were replaced, and fiberboard paneling on the interior walls and a fiberboard ceiling were added.

Minor roof repairs were made in 1984, and the roof and walls oiled, followed by significant conservation work in the 1990s. In 2006, ranger Joe Ventura packed shingles from Hockett to Quinn and patched a hole in the roof apparently dug by a bear in the winter. In 2011, the park’s historic restoration crew leveled the building, provided new sill logs and sturdy log shutters, and applied a new coat of stain. The cabin’s bunks also got long-requested new mattresses.

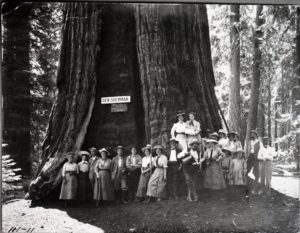

Today, when visitation to Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks is almost a thousand times greater than it was in 1907, the cabin that ranger Harry Britten built still stands and is still in use. For its local significance to military and conservation history, Quinn was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. It is the only ranger station remaining from the period when the U.S. Army administered Sequoia National Park. (The original Hockett Meadow Ranger Station, built in 1906, was replaced in 1934.)

The trail to Quinn Ranger Station is still well maintained, the nearby fishing is still good, visitors can still camp near Quinn Meadow and graze their riding and pack stock there when conditions allow, and the water from Soda Springs Creek still refreshes thirsty hikers and equestrians. Stop by to salute this long-lived rustic cabin, savor its stories, and realize that you are a part of its history when you’re traveling on the beautiful Hockett Plateau.

May, 2020

Sequoia and General Grant national parks were established in 1890. Sequoia was our country’s second national park (Yellowstone was established in 1872). On October 1, 1890, President Benjamin Harrison signed another bill, which almost tripled the size of Sequoia and created Yosemite National Park (#3) and General Grant National Park (#4).

“After heading south through a lush meadow generously sprinkled with wildflowers well into summer . . . you slowly curve east on the well-built trail . . . . Next ford a seasonal, incipient branch of Soda Spring Creek near a campsite above the trail and arrive at nicely preserved Quinn Cabin (8320′).” — J.C. Jenkins and Ruby Johnson Jenkins

” Its name heralds back to Harry Quinn, . . . . one of many settlers who made a living by sheepherding in the high sierra meadows. Quinn established a horse camp to pasture his pack stock that supported his sheepherding operations. . . . For the park and the military staff that patrolled it, keeping domestic sheep from the parks was a key goal.” — Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks

“A shovel lashed horizontally to the cabin just below the roof line demonstrates the depth of snow sometimes found by the surveyors who, after the long snowshoe trek in, have to shovel snow to uncover the cabin door. The hut is also used by the Hockett ranger on patrol; campsites can be found next to the meadow.” — J.C. Jenkins and Ruby Johnson Jenkins, 1995

“Quinn Patrol Cabin is 107 years old and I am pleased to have had a small role in its care and maintenance over the years. We found little sign of mice inside the cabin but could hear them in the attic. . . . The shingles on the roof at the northwest corner are either rotting or damaged by a bear.” — Ranger Joe Ventura, 2015

“As the [2011] Lion Fire approached, [the firefighters] conducted strategic burning operations near [the Quinn Ranger Station] to remove fuels in front of the main fire and therefore protect the cabin. Thanks to the excellent work of the firefighters, the natural and cultural values that help define why the national parks exist were protected.” — Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks

Directions:

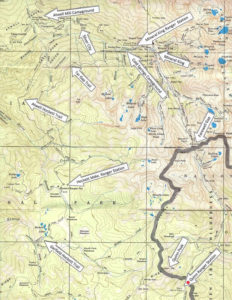

Quinn Ranger Station is about 13 miles south of Mineral King as the crow flies. It is accessible only by foot/stock trail; trailheads at several starting points provide access. (See trail map above in Quotes section.)

A) Most visitors start from the Mineral King area and travel via the Atwell-Hockett Trail, the Tar Gap Trail, or the Farewell Gap Trail.

For this approach, from Visalia, take Hwy 198 east through most of Three Rivers. Two miles before the main Sequoia National Park entrance, watch for the National Park mileage sign on your right, at the junction with Mineral King road. NOTE that Mineral King Road is narrow (sometimes single lane), steep, and winding, and is not recommended for RVs or trailers.

It is about 19 miles from this junction to Atwell Mill campground, trailhead for the Atwell-Hockett Trail; about 23 miles to Cold Springs campground, trailhead for the Tar Gap Trail; and maybe a half mile farther to the Mineral King ranger station, where you must pick up your Wilderness Permit prior to overnight stays in the Wilderness. Mineral King Valley, trailhead for the Farewell Gap Trail, is about 25 miles from the junction with Hwy 198.

B) Quinn Ranger Station is also accessible via the Garfield-Hockett Trail, which begins at South Fork campground, reached via South Fork Drive in Three Rivers.

From Visalia, take Hwy 198 east to Three Rivers and note the junction with South Fork Drive, on your right. However, do not exit here. You must first drive 5 more miles east on Hwy 198 to the main Sequoia National Park entrance and then continue to park headquarters at Ash Mountain to pick up your Wilderness Permit prior to any overnight stay in the Wilderness.

Then return to South Fork Drive and follow it east for 12.3 miles. The paved road ends a short distance before you reach South Fork Campground, and a rough dirt road, not recommended for vehicles with low clearance, continues to the campground area, where you will find the sign for the Garfield-Hockett Trail.

NOTE: Severe winter storms in 2022-2023 destroyed South Fork Campground and wrecked the segment of the road on National Park land. There are now no facilities at all in the campground area and the road is still impassable in 2024. Be sure to contact the Park for current information before attempting to access Park trails via South Fork Drive.