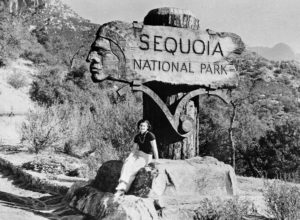

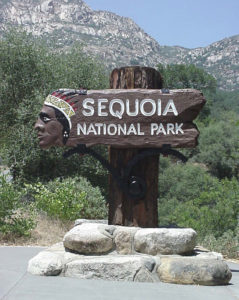

Of the tens of millions of photographs taken in Sequoia National Park each year, perhaps the most popular man-made subject is the iconic Indian Head sign that welcomes visitors to the park about a quarter mile up the road from the Ash Mountain entrance station. But why does the sign depict an Indian instead of a Big Tree? And what does this Indian have to do with a sequoia?

Part of the answer might be traced to Stephan Friedrich Ladislaus Endlicher. A leading Austrian botanist, ethnologist, and linguist, Endlicher, in 1847, scientifically classified the coast redwoods and published Sequoia as their genus name. However, he left no record of the reason for this name, leading to much speculation ever since.

When the massive redwoods of the Sierra Nevada were discovered in the early 1850s, they were originally given the scientific name Wellingtonia gigantea, but after further study revealed their similarity to the coast redwoods, the Sierra’s Big Trees became known as Sequoia gigantea. (The coast redwoods are now known as Sequoia sempervirens, and ours as Sequoiadendron gigantea.)

In 1868, Josiah Dwight Whitney, California’s state geologist (for whom Mt. Whitney is named), published The Yosemite Book. In its chapter on “The Big Trees,” Whitney wrote, “The genus was named in honor of Sequoia or Sequoyah, a Cherokee Indian . . . known to the world by his invention of an alphabet and written language for his tribe.” In a footnote, Whitney explained that Endlicher had seen an article about Sequoyah in a magazine, “The Country Gentleman,” which led him to use the name Sequoia. However, that magazine’s first issue did not appear until 1852, three years after Endlicher died, and scholars have been unable to document Whitney’s conclusions.

More recently, it has been argued that Endlicher named the genus “Sequoia” because it is derived from the Latin for “sequence,” and the new genus fell in sequence with the other four genera in his suborder. But unless long-lost papers of Endlicher’s turn up stating his reasons for the name, these theories will remain speculation.

Nevertheless, the idea that this great American tree was named for a great Native American has been widely repeated since Whitney’s time. And that’s why the Sequoia National Park entrance sign features an Indian, although he looks nothing like the real Sequoyah.

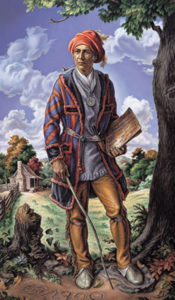

Portraits of Sequoyah depict him in a red, striped turban, a white shirt, and a blue jacket or coat, often wearing a red cravat and his silver medal, holding a copy of his syllabary, and smoking a small pipe with a long slender stem. So, where did the image of the Indian wearing the feathered head-dress on the Sequoia sign come from?

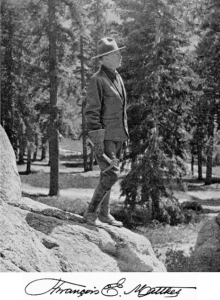

In 1931, while working in Sequoia as a National Park Service Landscape Architect, Merel S. Sager designed an entrance sign for Ash Mountain featuring an Indian, possibly Sequoyah. This sign, like the current one, was carved out of redwood, but was only about a third as big — and it was soon replaced.

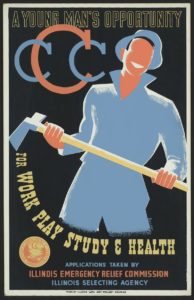

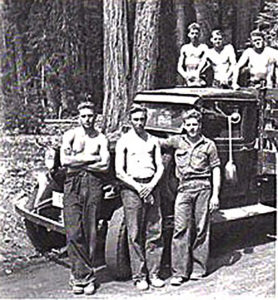

By 1935, the next Sequoia National Park landscape architect, Harold G. Fowler, decided to improve the entrance sign. To execute his idea, he looked to the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) enrollees employed in Sequoia at the time. (Hundreds of thousands of unemployed young men across the nation were enrolled in the CCC, established by President Roosevelt’s New Deal in 1933 to provide relief from the Depression by putting them to work in conservation projects on public lands.)

In CCC Company 915, Fowler found George Walter Muno, a native of nearby Lindsay. Muno had demonstrated woodworking skills in his high school industrial arts class, had taken a wood carving class offered to the CCCers, and had carved the High Sierra Trailhead marker at Crescent Meadow.

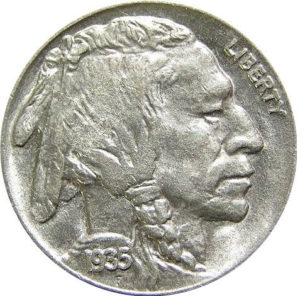

Muno agreed to carve the big new sign. Up in the Giant Forest the two men found a piece of fallen sequoia wood large enough to hold Fowler’s idea. Then Fowler outlined on it in blue chalk the image he wanted Muno to carve. The model for it was in his pocket — the iconic profile of an American Indian on the obverse side of the “Buffalo Nickel,” first issued by the U.S. Mint in 1913.

Muno spent several months in Giant Forest, carving the Indian head and routing out the foot-high letters on the massive redwood slab, that was ten feet long, four feet high, and a foot thick. Meanwhile, the park machinist at Ash Mountain made the beautiful curved metal bracket to hold up the sign and CCC crews prepared the supporting log pylon and masonry. The pylon, a fifteen-foot sequoia trunk, four feet in diameter, rests on a two-tiered boulder masonry platform approximately ten feet square. Early in 1936, all the pieces were put together and “Sequoyah” began welcoming visitors to Sequoia National Park. Many stopped to have their pictures taken with the monumental Indian.

In 1978, the Ash Mountain “Indian Head” Entrance Sign was listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its significance in the fields of art, landscape architecture, and social humanitarian endeavor. The nomination form concluded that, “Excepting required maintenance, no alterations should be allowed.”

However, the sign has been altered more than once since it was erected. Originally unpainted, it was stained a redwood color in the 1950s and Sequoyah’s face was painted. In 1964, the sign was moved about 100 yards, due to construction work on the entrance station, and a second log pylon, which had originally stood across the road from the Indian sign’s pylon, was destroyed.

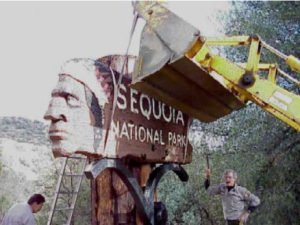

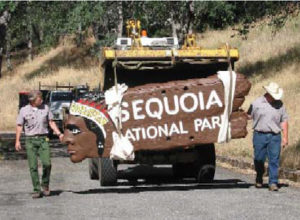

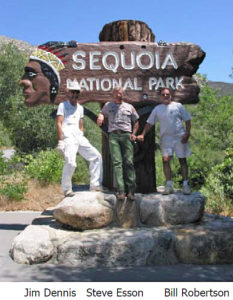

From January to May, 2002, the sign was removed from its support for major restoration work, carried out by Steve Esson, Park Sign Maker, assisted by painters Bill Robertson and Jim Dennis. First, its paint was stripped off and the sign was allowed to dry out; it shed about 100 pounds of water weight that had accumulated over 65 years outdoors. Rot damage was removed. Cracks and insect damage were repaired. Epoxy was carefully applied to fill the voids and seal the 450-pound slab while maintaining its weathered character.

After being painstakingly repainted, the sign was re-installed on May 24, 2002. And so “Sequoyah” — whether or not he was known to Endlicher, or considered by Sager or Fowler — continues to greet the millions of visitors streaming into the park at Ash Mountain, many of whom will stop to record their encounter with this famous face of Sequoia National Park.

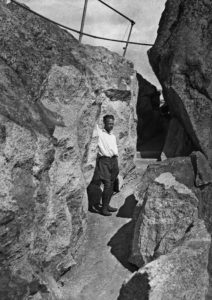

Note: See related article on Sager’s enduring work: Moro Rock Stairway.

Merel S. Sager pioneered “National Park Service rustic” architecture. He began working for the Park Service in 1928 and became Chief Landscape Architect. His works for General Grant National Park and Sequoia National Park in the 1930s included the Moro Rock Stairway and several structures at Giant Forest Village-Camp Kaweah Historic District.

“George Muno began with KP duty then served successively as dining room orderly, road worker, truck driver, truck master, and tool, equipment and supply clerk. Because of his swimming ability, George was given the assignment of diving below the surface of the river to plant dynamite prior to bridge construction.” — Mary Anne Terstegge

“. . . when I was asked to do a nickel, I felt I wanted to do something totally American — a coin that could not be mistaken for any other country’s coin. It occurred to me that the buffalo, as part of our western background, was 100% American, and that our North American Indian fitted into the picture perfectly.” — James Earl Fraser

Sequoyah, aka George Gist, born in Tennessee, never attended school or learned to read or write English, but became a talented blacksmith and silversmith, and then fought under U.S. General Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812. In business and in the military, he saw the tremendous advantage of the “talking leaves,” the pieces of paper covered with writing that carried clear messages across distance and time.

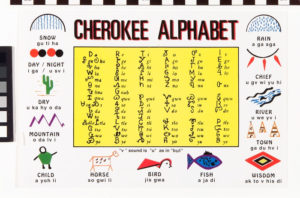

Sequoyah determined to create a written Cherokee language. After 12 years, despite many false starts, and laboring under ridicule and accusations of witchcraft, he demonstrated a phonetic syllabary of 85 symbols, each representing a unique syllable and sound. In 1821, the Cherokee Nation adopted Sequoyah’s system. Soon thousands of Cherokee people learned to read and write in their own language. Over 20,000 people speak Cherokee today, and Sequoyah’s syllabary is still in use.