Although only about twenty percent of Kings Canyon National Park falls within Tulare County, the saga of how this superb mostly wilderness national park came to be is very much a Tulare County story. Tulare County residents, in fact, played key roles in the decades-long campaign to create the park.

Like both Sequoia National Park and Sequoia National Forest, the area that is now within Kings Canyon National Park was placed within the original Sierra Forest Reserve in 1893. In 1908, that vast reserve was broken apart and its several portions re-designated as national forests. After that date, what later became the Tulare County portion of Kings Canyon National Park fell within the newly created Sequoia National Forest.

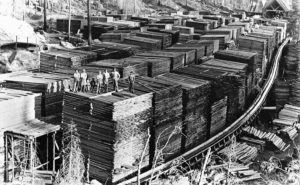

From the beginning, although both were conserved as public lands for the public good, areas identified as national forests and national parks drifted in very different directions. National Forests fell under the control of the United States Forest Service, an agency in the U. S. Department of Agriculture. Forest Service management policies emphasized using land for public benefit. Potential uses included grazing, mining, and logging – all to be carried out in a responsible manner. Agency policy also emphasized dams, reservoirs, and hydroelectric development, undertakings that seemed to many to be well-suited for the mountain gorges of the Kings River portion of the Sierra Nevada.

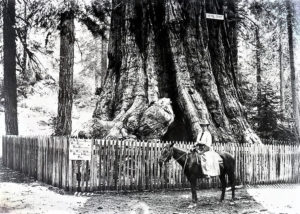

At the same time, areas designated as national parks evolved to have their own unique mission. In 1890, Congress had created Sequoia and General Grant national parks in Tulare County as well as Yosemite National Park to the north. All three were envisioned as nature preserves – places where natural features would be left undisturbed and human use would be limited to recreation and inspiration. Management of these federal parks fell to the Department of the Interior.

Each of these two visions reflected the hopes and dreams of its supporters, and Congress eventually created a federal agency to manage each system. The Forest Service came into existence in 1905, and the National Park Service, an Interior Department agency, was created in 1916. The competing land management visions represented by the two agencies both made sense. Clearly, America had lands that ought to be used for the benefit of society as well as special places that ought to be protected for their beauty. Inevitably, however, these two agencies, each with its own mission, sometimes set their sights on the same places. The Kings River portion of the High Sierra was such a place.

The battle over the fate of the Kings Canyon region began early. The men who had led the campaign to create Sequoia National Park in 1890 dreamed almost from the beginning of enlarging the park to take in more of the spectacular High Sierra. They were particularly interested in two scenic regions: the Kern Canyon/Mt. Whitney area immediately to the east of the 1890 boundaries of Sequoia National Park and the Kings Canyon region to the northeast of the existing park.

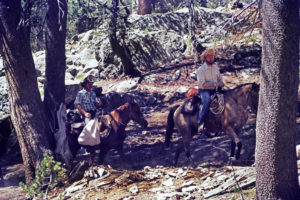

The Sierra Club, in those days a San Francisco Bay Area-based mountaineering organization, began taking large groups into these two areas in 1902, when it brought over two hundred persons into then-remote Kings Canyon for several weeks. The club returned, always with large groups, to either the Kings Canyon or the Kern Canyon in 1903, 1906, 1908, 1910, 1912, 1913, and 1916. These trips exposed hundreds of people to the beauty of these areas and laid the foundation for political action leading towards their protection.

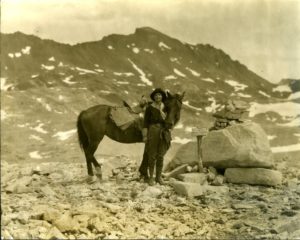

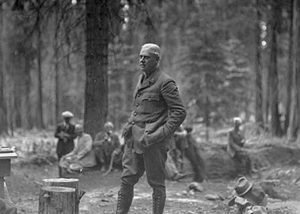

In 1915, the Department of the Interior recruited Chicago businessman Stephen T. Mather to take over administration of the national park system and lead the campaign to create a national park agency – the National Park Service. Mather, a native of California, had strong ties to the Sierra Nevada and had taken part in the Sierra Club’s 1912 outing to the Kern Canyon. On that trip, like many others, he had become convinced that Sequoia National Park must be enlarged. When he joined the Interior Department in 1915, he put this enlargement high on his list of goals. In the summer of 1915, Mather organized an overtly political pack trip into the Kern Canyon/Mt. Whitney region. Visalians George Stewart and Ben Maddox met the group when it first assembled in Visalia and made clear their support for park enlargement.

Mather became the first director of the newly created National Park Service in 1916, and in this role he continued his efforts to enlarge Sequoia National Park. The Forest Service prized the area highly, however, and worked hard to keep both the Kern Canyon/Mt. Whitney and Kings Canyon regions within the Sequoia National Forest. Finally, after a decade of contentious political debate, a compromise was struck. In July 1926, Sequoia National Park was more than tripled in size to include the Kern Canyon and Mt. Whitney areas. Kings Canyon, however, remained within the national forest systems and open to development.

The Forest Service, pursuing its mandate to find uses for its lands, began to make plans for the development of the Kings River region. In the late 1920s, in cooperation with the State of California, the Forest Service approved the construction of a modern highway into the region, and the following year the Federal Power Commission issued a report making clear the potential of the area as a locale for reservoirs and power plants. As early as 1920, the city of Los Angeles had also filed claims for dam sites and reservoirs on the Kings River. There were even rumors that the Los Angeles interests intended to tunnel under the Sierra Crest to divert Kings River water eastward into its Owens Valley Aqueduct.

All these proposals eventually reinvigorated those who still wanted to place the Kings Canyon and its surrounding high country within a national park. In the middle 1930s the Sierra Club resumed its campaign. This time the goal was not to add the area to Sequoia National Park but rather to create an entirely new park centered on the great glacial canyon of the Kings River. Local opinion split between those who wanted dams and those who thought the area worth protecting for its natural beauty and spectacular scenery. Nearly everyone in Central California agreed, however, that allowing the water to go to Southern California would be a mistake.

Eventually, the fight over whether there should be a national park in the Kings Canyon region came down to a political dispute between two local elected officials. The U.S. congressman from Fresno, a Republican named Bud Gearhart, led the campaign to create the park. He was opposed by Representative Alfred Elliott of Visalia, a Democrat.* The Sierra Club sided with Gearhart, and the Forest Service worked hard to help Elliott. The final vote could have gone either way, but Elliott overplayed his hand when he charged that Gearhart was accepting illegal donations from national park supporters. Gearhart, in an impassioned speech on the floor of the House of Representatives, successfully demolished Elliott’s accusations, and the bill passed the House shortly thereafter.

President Franklin Roosevelt signed the legislation creating Kings Canyon National Park in March 1940. The political deal that led to the creation of the new national park also committed the federal government to building a dam on the lower Kings River at Pine Flat. That dam was constructed between 1947 and 1954.

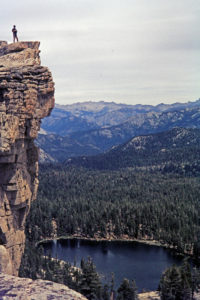

The highway into Kings Canyon that the Forest Service commissioned in the late 1920s finally reached the canyon floor in 1939. Today, as California State Route 180, that route provides a scenic drive into the heart of Kings River country. The highway ends just past Cedar Grove on the floor of Kings Canyon. The rest of the main section of Kings Canyon National Park, including all of it that falls within Tulare County, remains as un-roaded wilderness. It took half a century, but the 1890 dream of Visalian George Stewart that the Kings Canyon region should be part of a national park eventually did come to pass. Today, Kings Canyon National Park stands as the great wilderness park of the Sierra Nevada.

* Observers of contemporary politics in Central California may be surprised to read of a Republican leading a campaign to create a national park while a Democrat fought against the park. Over the decades, the two parties have changed positions several times on these matters. The greatest presidential advocate ever for public lands, for example, was Republican Theodore Roosevelt, and both the National Environmental Policy Act and the Endangered Species Act were signed by Republican Richard Nixon.

May, 2014

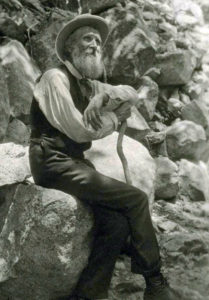

“Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life.” – – John Muir, 1901

“When one looks at the great trailblazers of the American preservation movement, many names grace Kings Canyon. John Muir, of course, stands at the summit with veneration. At his side stands Little Joe LeConte . . . . There were countless other giants, among them [Theodore] Solomons, [Walter “Pete”] Starr [Jr.], [Stephen] Mather, [Horace] Albright, [William] Colby, [Ansel] Adams, and [David] Brower, all of whom heeded the call to preserve and protect the best of the American earth.” — Gene Rose

“[All} of this wonderful Kings River region, together with the Kaweah and Tule sequoias, should be comprehended in one Grand National Park. . . . Let our law-givers make haste before it is too late to set apart this surpassingly glorious region for recreation and well being of humanity, and all the world will rise up and call them blessed.” – John Muir, 1891

“[I]n 1905, [Gifford] Pinchot orchestrated the transfer of the [forest] reserves from the Interior Department to the Department of Agriculture — an event usually recognized as the genesis of the modern Forest Service . . . . An advocate of utilitarian conservation, [Pinchot] believed that all the resources on the public lands should be available for use and development — as long as those uses were sustainable . . . centered on the magnanimous slogan, ‘the greatest good for the greatest number and in the long term.’ Multiple use was his byword.” — Gene Rose

“It was a treasure house of riches far greater than any hidden beneath the surface. Cutting the sky the most colossal of all Sierra crests reared its adamantine spires, walling a world of can[y]ons, peaks, dashing ice torrents, unassailable heights, green parks bordered and starred with exquisite Alpine flowers, which fringed even the snow banks . . . awful, austere, beautiful in its scarred and chaotic majesty. A world to behold: no pen nor brush may picture it. The transcendent glory of the mighty Sierra Nevada.” — Frank Dusy

“[I]n 1912, [Stephen] Mather, who became the first director of the National Park Service, made the first of his own mountain trips in the Sierra [where] he met Colby and other Sierra Club members. One of the highlights of Mather’s life was the opportunity to have a long talk with the legendary [John] Muir . . . [who] . . . interested him in another of his vital concerns—the addition of vast majestic Sierra areas to Sequoia National Park or, better still, the creation of a new park between Yosemite and Sequoia.” — Horace Albright

“The Mather Mountain party . . . gathered for the first time on . . . July 14, 1915 in Visalia, California. . . . [A]t the Palace Hotel . . . a dinner party was held that first night, hosted by local businessmen. . . . After dinner, [George] Stewart [Visalia attorney and long-time editor of the Visalia Weekly Delta] gave an informative talk on the giant sequoias. [Ben] Maddox [owner and publisher of the Visalia Daily Times] followed with a summary of the proposed enlargement of Sequoia National Park. . . . Robert Marshall [Chief Geographer of the U.S. Geological Survey] . . .gave a rousing pep talk encouraging the people of Visalia to promote a bigger and better Sequoia National Park. Then Mather sent his guests off to the last indoor beds they would see for several weeks.” –Horace Albright and Marian Schenck

“[T]he Sequoia-Whitney country is God’s own country, . . . and the mountains assure me that . . . the [Mather Mountain] . . . party will sing of the ‘Greater Sequoia’ until all the world shall have heard them and will unite to preserve this really wonderful region for the ‘benefit and enjoyment of the whole people’ for all time.” — Robert Marshall (1915)

“The immediate effects of the mountain party were local: elimination of toll roads; publicity creating strong support in the San Joaquin Valley for extension of Sequoia or the creation of a new park to encompass the Kings and Kern canyons; purchase of the Giant Forest, the heart of Sequoia; fifty thousand dollars from the federal government; twenty thousand from Grosvenor and the National Geographic Society; precedent for private parties to purchase lands and donate them to the government. . .; and impetus for the U.S. government to aid in the completion of the John Muir Trail.” — Horace Albright after Mather Mountain Party expedition

“[T]he publicity about the mountain party, through newspapers and magazines, focused attention on the parks and the need for a national park service. The newly found belief in conservation and the concept of “wilderness” was generated from influential men in our group” — Horace M. Albright after Mather Mountain Party expedition

Directions:

Coordinates: 36° 47′ 21.41″ N, 118° 40′ 22.3″ W36.78928, -118.67286

From Visalia, take Hwy 198 east via Three Rivers to enter Sequoia National Park and proceed on the Generals Highway to the Grant Grove area in Kings Canyon National Park.

Alternately, take Hwy 63 north from Visalia to Hwy 180 east to enter the Grant Grove area of Kings Canyon National Park.

From Grant Grove you can continue 30 miles east on Hwy 180 down the canyon to the Cedar Grove area and 6 more miles to Road’s End.

Note the possibility here for a fine loop trip.

Note: Vehicles longer than 22 feet should take Hwy 63 to Hwy 180. The road between the Foothills Visitor Center (east of Three Rivers) and the Giant Forest Museum is too steep, narrow, and winding to accommodate longer vehicles.