[

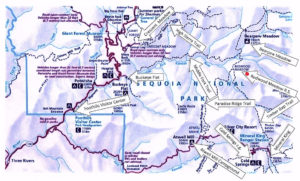

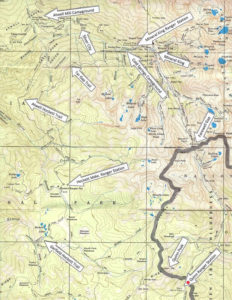

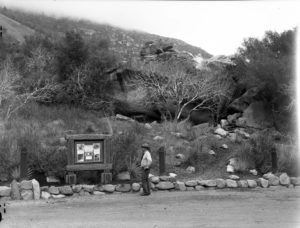

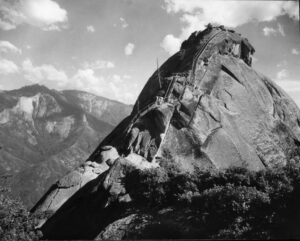

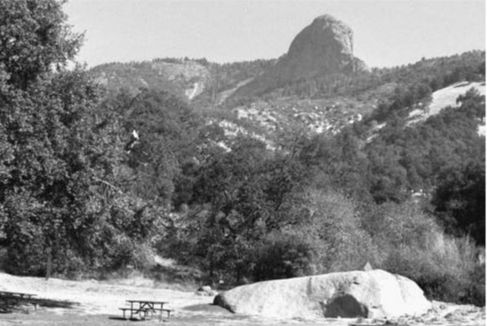

Over a million people a year walk, hike, or ride horseback on the amazingly diverse trails of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. From a short, easy stroll into a magnificent giant sequoia grove to a strenuous backpacking trip to the summit of rugged Mt. Whitney, the highest peak in the 48 contiguous states, these paths offer people of all ages, inclinations, and abilities a multitude of opportunities to experience the parks’ wonders in the very best way: at a walking pace, free to pause whenever they please, immersed in the sights, scents, sounds, and thrills of the wild world.

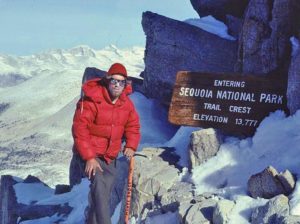

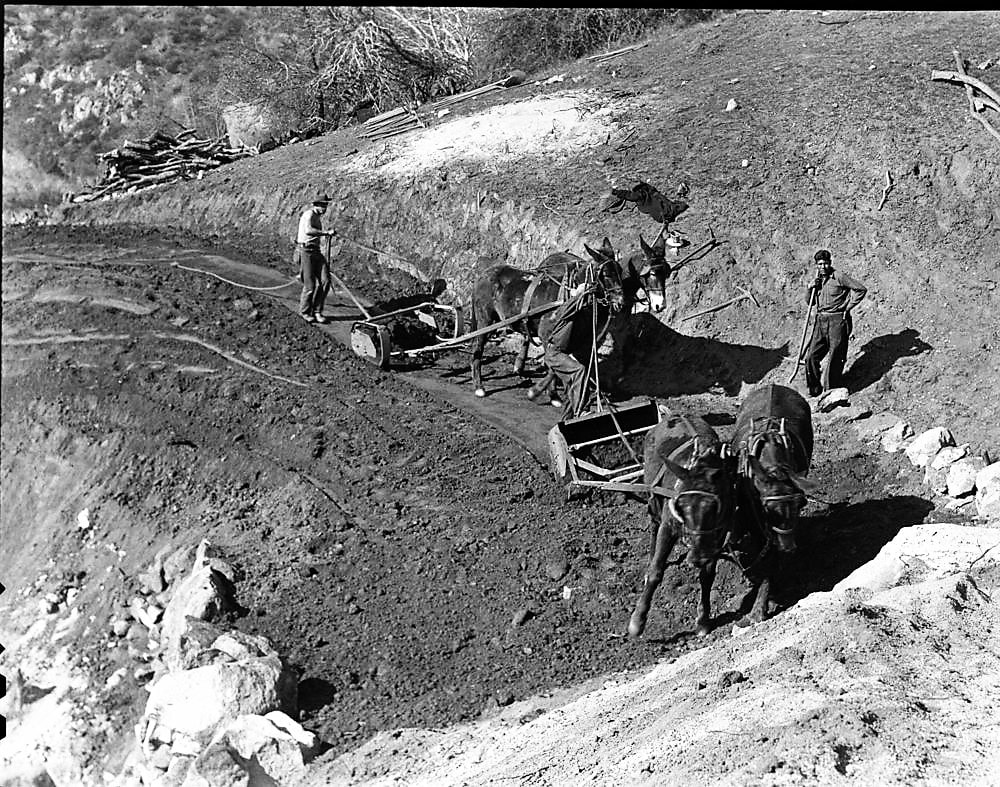

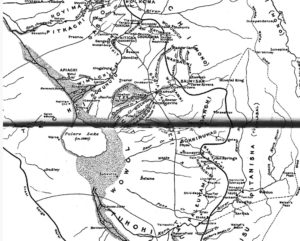

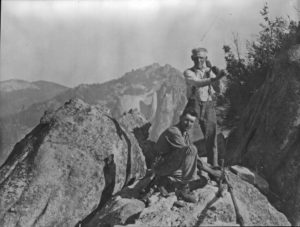

Ranging in elevation from less than 2,000 feet up to 14,500 feet, the trails traverse over a thousand miles to connect the major features and extraordinary environments of these spectacular parks. Who builds these beckoning byways, and who maintains them in the face of floods, fires, avalanches, rock slides, falling trees, deep snows, and thoughtless trail-cutters?

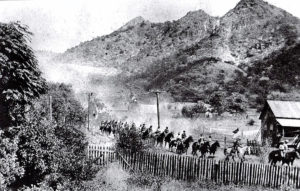

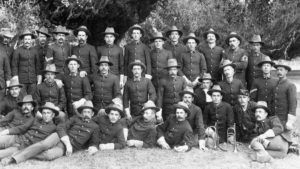

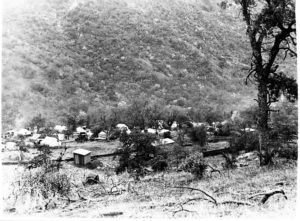

Since the National Park Service was established in 1916, this essential work has been carried out primarily by NPS Trail Crews (while Civilian Conservation Corps workers contributed a tremendous amount of trail maintenance from 1933 to 1942). Beginning in the 1970s, the parks have also been partnering with volunteer service organizations such as the Youth Conservation Corps to help maintain the miles of trails being “loved to death” by the increasing national interest in outdoor recreation.

It’s not easy to get hired on to a Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks trail crew. First, applicants must realize that their work locations may be in any area of these two parks, which are 93% wilderness and span “an extraordinary continuum of ecosystems, arrayed along the greatest vertical relief (1,370 to 14,495 feet elevation) of any protected area in the lower 48 states.”

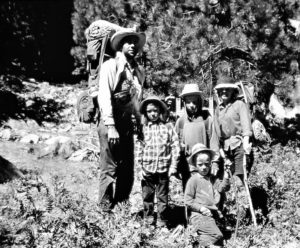

Trail crew positions require wilderness travel and camping skills; the ability to hike at high altitude for extended periods of time and up to 20 miles a day while carrying backpacks, tools, and supplies weighing at least 50 pounds; and the ability to perform masonry and carpentry work in addition to a full spectrum of basic trail work, including clearing fallen logs, removing encroaching vegetation, digging to maintain drainage structures or trail tread, and moving materials of all shapes and sizes in rugged terrain.

Are you still interested?

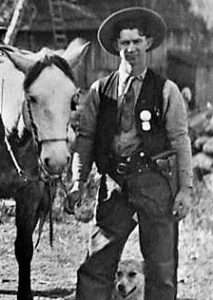

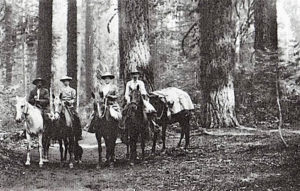

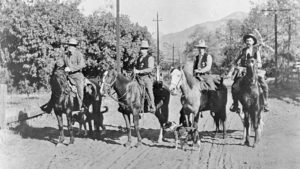

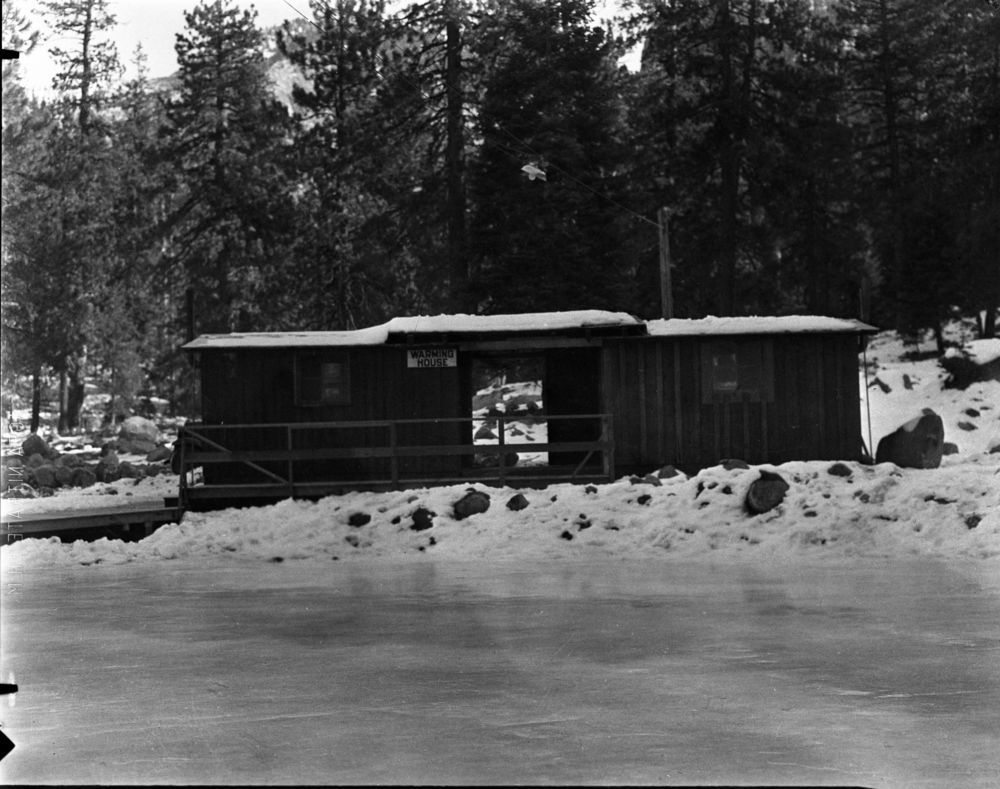

Trail crews in these parks work outdoors in temperatures varying from over a hundred degrees down to near ten degrees, and may experience heavy rain, hail, and falling snow. Typically, the work environment is hot, dusty, dirty, and sometimes noisy. Working long hours, hiking or riding horseback in rough country, crews may encounter hazards such as poisonous plants and animals and high, cold, swift water at stream crossings.

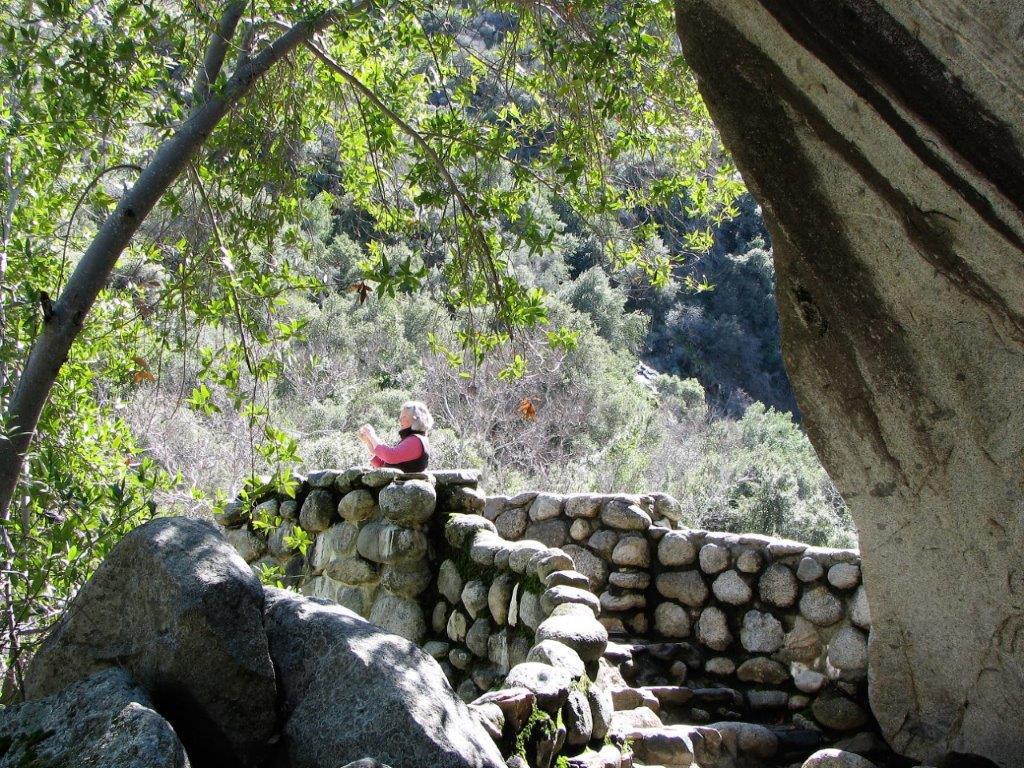

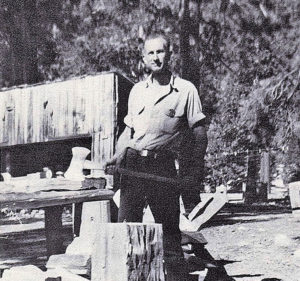

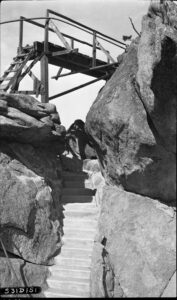

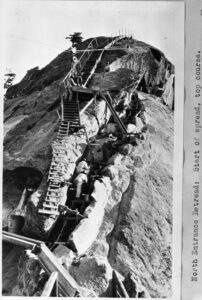

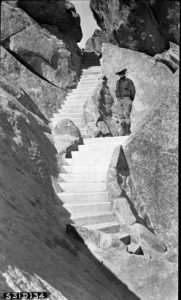

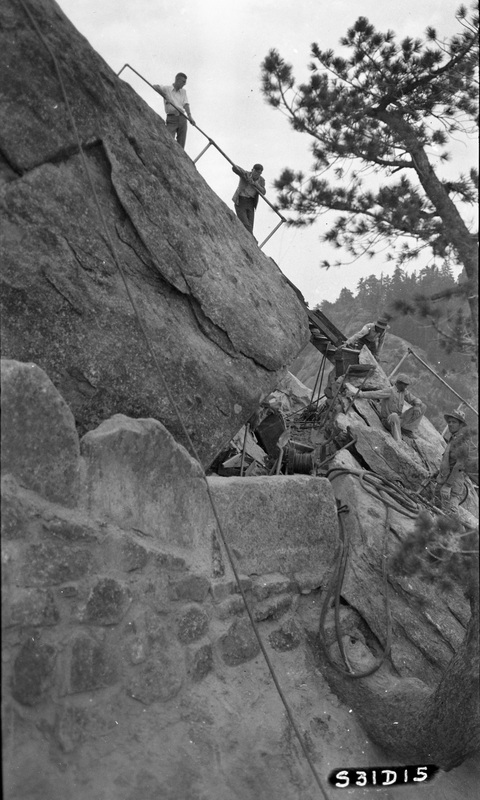

They construct, repair, and maintain bridges, abutments, aesthetically pleasing rock walls, walkways, causeways, trail tread, water bars and retainer steps. Their tools include rock bars and drills, jacks, chisels, a variety of saws, timber tongs, draw knives, planes, and other masonry and carpentry tools, which they also clean and repair.

Heavy physical effort is required in using both hand and power tools; frequently lifting , carrying, or rolling objects such as rocks and logs weighing over 100 pounds; moving slabs and boulders weighing several tons with rock bars; using hammers to crush or shape rock; and shoveling extensively.

To provide for visitor access and safety, the crews build all kinds of trails, from accessible trails meeting Americans with Disabilities Act guidelines in some frontcountry sites to trails that climb to high mountain peaks in the backcountry. Laws including the National Historic Preservation Act, the National Trail System Act, the Wilderness Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the Clean Water Act all apply in Sequoia and Kings Canyon.

These laws require trails to avoid damaging habitats or disrupting important lands, waters, or historic or prehistoric sites. To protect cultural and natural resources, crews may route trails around sensitive areas, construct boardwalks over wetlands, or seasonally close trails during nesting or migration times.

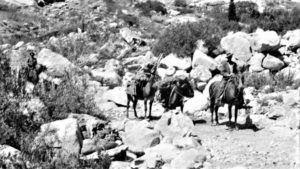

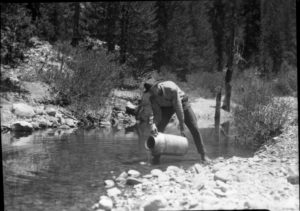

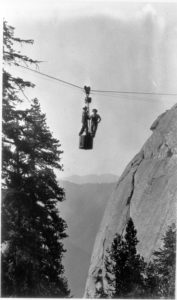

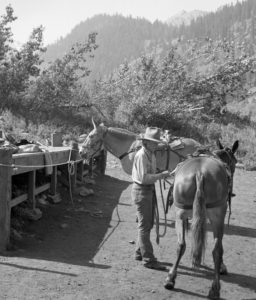

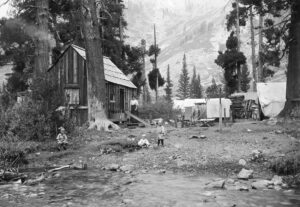

Crew members must also have the ability to live and work effectively in remote, primitive backcountry areas in close contact with small numbers of people for two to twelve weeks at a time. Crews typically consist of three to ten NPS workers, and a Cook for work in the backcountry. Crews may be supplemented by work groups from the California Conservation Corps, the Student Conservation Corps, Volunteers-in-Parks, and other programs. To support backcountry projects, pack trains periodically bring in food, mail, supplies, and equipment.

Would you like to gain the extra skills and responsibilities of a crew leader?

Trail crew leaders not only perform the full spectrum of trail work themselves. They also have to perform inspections, surveys, and inventories of facilities for maintenance needs to provide for accurate planning and scheduling of work, and make informed recommendations for operational improvements. They plan, lead, and supervise the crew’s work, provide training, emphasize and monitor safety, and, of course, write reports.

Additionally, crew leaders must possess and maintain an NPS Blasters License because they serve as Blaster in Charge to remove obstacles such as logs and rocks from trail tread, to quarry stone for masonry work, and to establish trail bench in bedrock areas. They also assist in mule and horse packing operations by riding on mountainous trails, preparing supplies and materials for mule transport, tying on loads, and leading pack animals. To move big boulders and logs in the wilderness, they set up and use human-powered winches and rigging such as high-lines.

The crews often coordinate with backcountry rangers to determine and prioritize projects in their work areas, and frequently assist park visitors by providing information about trails and weather, helping with communications and directions, and even participating in searches for persons reported missing or overdue.

Have you had the opportunity to thank a trail crew yet? Next time you’re traveling on some part of the tremendous trail network in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, pause to reflect on what you’re walking on and appreciate the work of the dedicated, skillful men and women who have labored for such long hours in such difficult conditions to make your journey as smooth and safe as they can.

As a young worker from the Eastern Sierra Conservation Corps serving in our parks put it, ” It takes tremendous grit and passion for a member of a national park trail crew to thrive. Though the days may be long, the physical demands arduous, and the unexpected challenges difficult to navigate, one thing is for sure: serving on a trail crew guarantees an unforgettable experience.”

(If you’d like to try to join a national park trail crew, check usajobs.gov and search for “maintenance worker trails”.)

May, 2020

NOTE: To find the “History of the Wilderness Trail System of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks,“ see Granite Pathways, by William C. Tweed (Three Rivers, CA; Sequoia Parks Conservancy, 2021).

[

“Working at a National Park teaches you confidence and perseverance. I spent six months with the Backcountry Trails Program in Kings Canyon National Park . . . . [T]the commute was the worst part. . . . I had to move as fast as I could with a pack and tools — shovels, McLeod’s, loppers, Pulaskis, sledgehammers, 20-pound rock bars, grip hoists — uphill, nonstop, for miles . . . at elevations exceeding 13,000 feet. We were the highest-elevation trail crew in the country that year . . . .” — Anna Mattinger, 2018

“Trail crews frequently work in isolated areas where medical facilities are not readily available, and transportation of an injured person is often difficult and dangerous. Good safety practices demand that each crew member keep in good physical condition and maintain a high level of safety consciousness at all times, in camp as well as on the job. . . . [E]very employee must be his or her own safety inspector on the job, work in a safe manner, and point out unsafe practices to other crew members.” — NPS Trails Management Handbook

“You’ll learn to fear lightning when you’re working above the timberline. You’ll learn drystone masonry and how to build rock walls and stairs without cement. The standards are high: If your work can’t be expected to withstand a century of continuous foot traffic and weather, it isn’t good enough. . . . . Doing this stuff, you’ll learn that granite weighs around 170 pounds per cubic foot.” — Anna Mattinger, 07/18/18

“It has to be sturdy enough to take the steady thudding of boots and hooves without disintegrating. It has to be angled so that the water pouring down a slope doesn’t course through it and turn it into a stream. It has to be high and dry enough that boots and hooves don’t sink knee-deep in mud. Oh, and it can’t have fallen trees blocking it. When about 700 trees . . . were left sprawled across the 10 -mile trail . . . by winter’s high snows and spring’s high winds, someone had to clear them away.” — Felicity Barringer, 2011

“The trail was still going down as I passed some huge logs, freshly cut into pieces. The smell of fresh sawdust still hung in the air. I am always amazed about the people who do all this work: maintaining the trails, fighting fires, building bridges and cutting up big trees that obstruct the trail. I realized that they must bring all their tools, probably by mules or horses, but still they must hike days on the same trail as I was doing.” — Overseas Hiker, 2018

“[T]he regular National Park Service trail crews were supplemented for six weeks by a 14-member crew organized by the California Conservation Corps. The crew included seven veterans (some recruited through the three-year-old Veterans Green Jobs nonprofit) and was part of a pilot program to give former service members training in land conservation.” — Felicity Barringer 2011

“The first few weeks on the job, I contemplated quitting . . . . I am glad I did[n’t], because I learned so much. I was able to participate in creating a bridge over a stream–from felling the tree to using a grip hoist to set the bridge into place. I also was able to help in transforming a rocky slope into a usable trail. I got to rework trails so that water would run off them and erosion would be minimized. I believe these skills will be useful in a future career in landscape architecture.” — joinhandshake.com, 2018

“Performs carpentry work, primarily using heavy log and rough-sawn lumber, on trail structures such as log checks, foot-bridges, multi-use bridges, corrals, hitch rails, and boardwalks.” Use a chain saw to “fell, buck, notch, and/or shape both native and pressure treated logs in the maintenance and construction of bridges, water bars and retainer steps, crib walls and steps, . . . and in clearing trails of down trees and brush. — from NPS job description

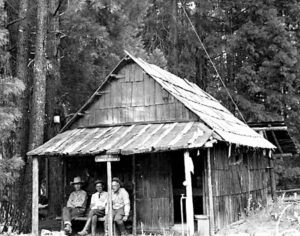

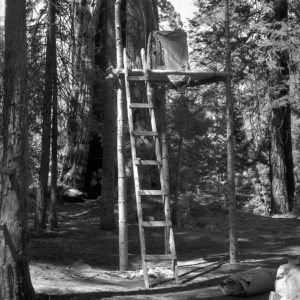

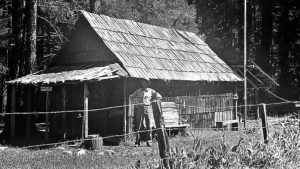

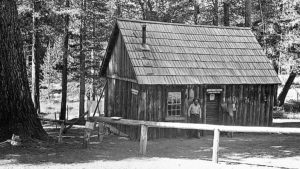

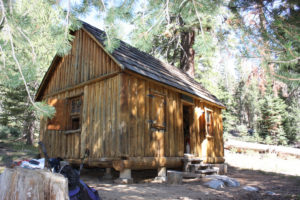

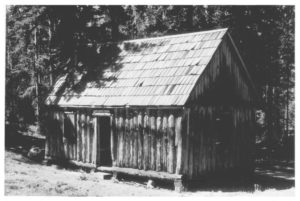

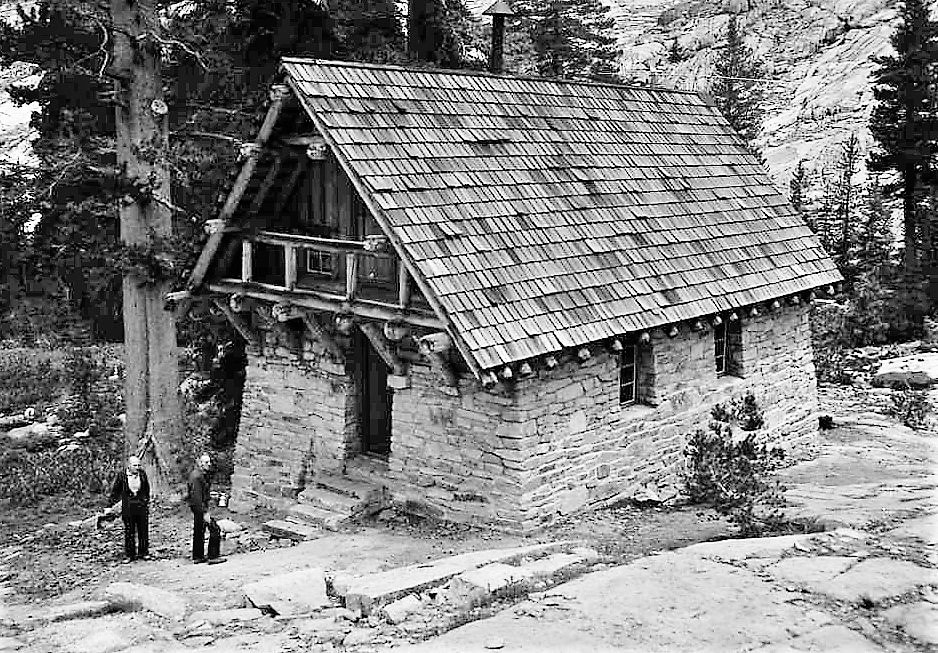

“In the summer of 1973, my backcountry crew and I were working at . . . Redwood Meadow . . . . An old fence, first built by the CCC . . . had long ago fallen into disrepair, so we started . . . replacing the rotten posts and stringing new wire. One afternoon . . . we uncovered an old metal bin [and] . . . found the carpentry tools the CCC had used to build the cabin at Redwood Meadow: double-bit axes, log carriers, drawknives, and a brace and bits. Their wooden handles were still dark from the oil and sweat of men working there thirty-five years earlier.” — Steve Sorensen, 2018

“[T]he [trail] crossing below [Redwood Meadow] . . . [needed] a series of wooden footbridges. . . . [A] lot of the satisfaction [in building the bridges] came from using those old tools . . . in the same way the CCC workers had used them long ago. . . . Before supper we’d hike down to Cliff Creek and jump . . . into a deep pool of clear water — the same place where the CCC boys had washed and played three decades earlier.” — Steve Sorensen, 2018

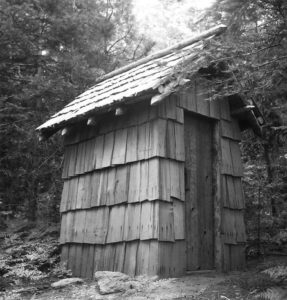

“During the trail crew visits . . . [w]ood was bucked up, split, hauled, etc. for the trail crew, Hockett ranger, wilderness seminar, and snow survey. Two new hitching rails were constructed . . . . One of the public outhouses was moved here at Hockett Meadow. Several days were spent . . . doing trail work (raking rocks) and on the new bridge near Horse Creek. ” — Lorenzo Stowell, Hockett Mdw. Ranger, 1992