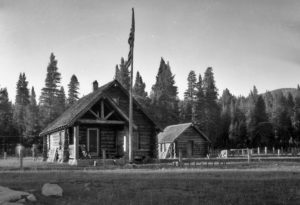

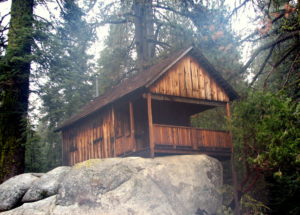

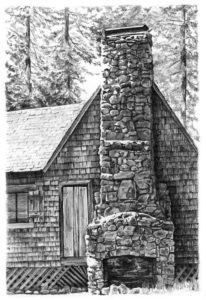

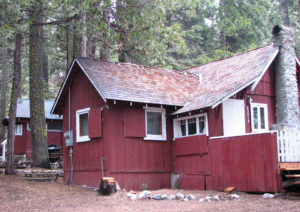

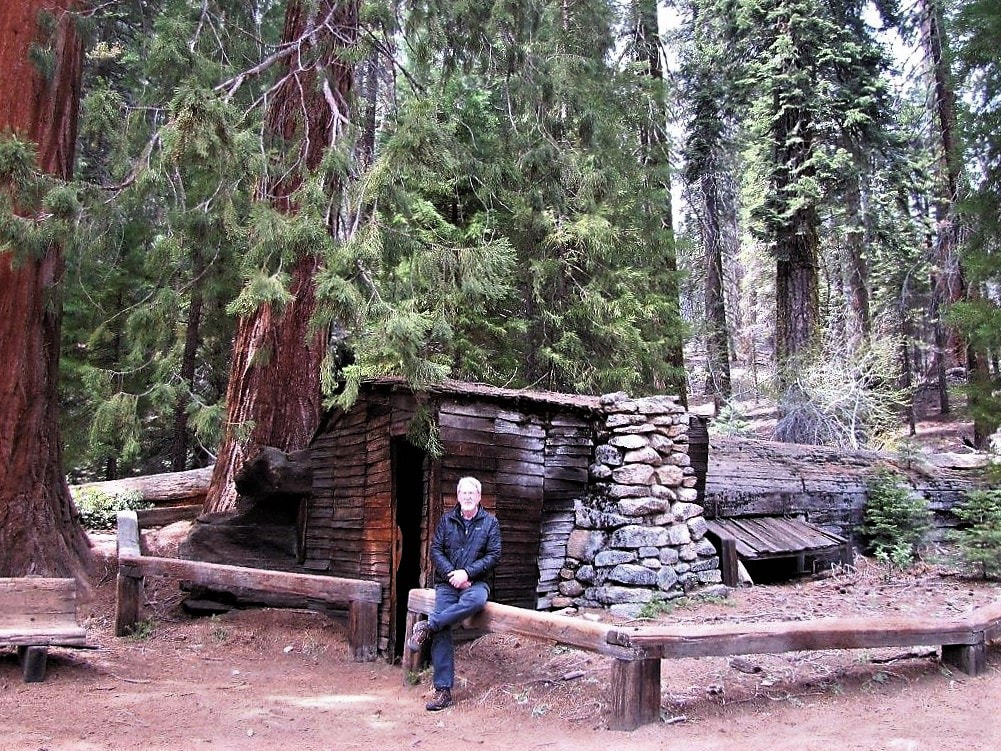

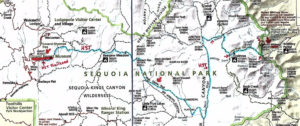

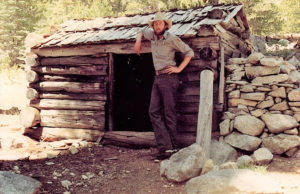

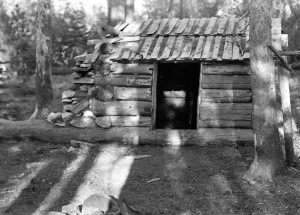

Sequoia National Park’s historic backcountry ranger stations and their adjacent barns, meadows, and nearby campsites serve the parks and the public in many ways. They accommodate not only rangers, but also trail crews, cultural resources crews, snow surveyors, occasionally monitors of meadows, water, wildlife, wildfires, and weather stations, and sometimes backcountry visitors in distress.

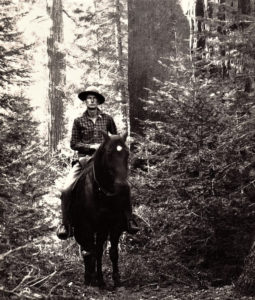

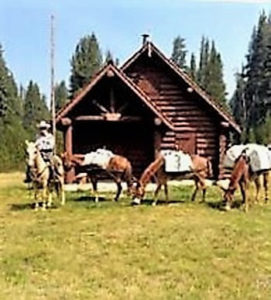

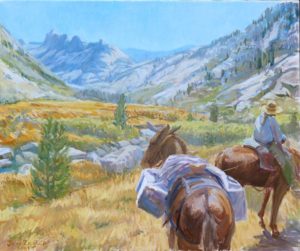

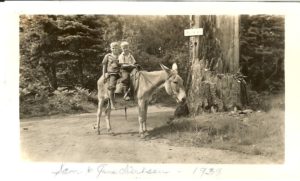

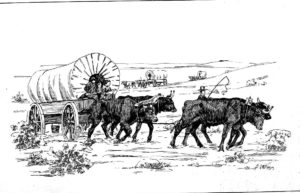

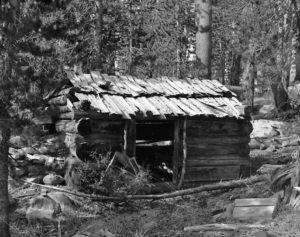

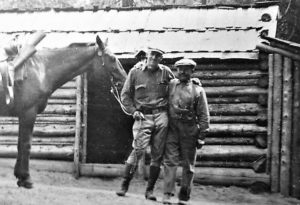

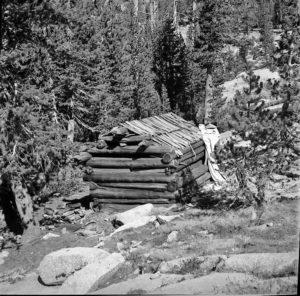

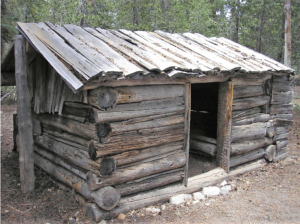

Their barns (also called tack sheds) store equipment and supplies used by these personnel, and their pastures provide grazing for their stock and, when conditions allow, for visitors’ animals also. Most of today’s backcountry visitors spend only a night or two in the campsites near these iconic cabins, but seasonal backcountry Wilderness rangers may be stationed in them or patrolling to them from May into October.

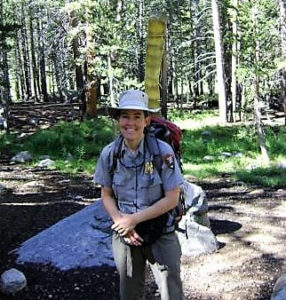

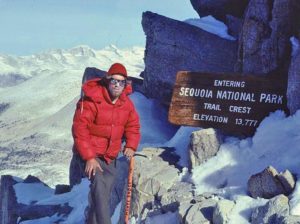

This strenuous backcountry work is often carried out far from many comforts, conveniences, and sometimes even company. It can be dangerous, sometimes cut off from communications, and often far from help. Many of these Park employees are seasonals, whose paychecks start and end depending on when the snow melts enough to allow access to their work sites — and when autumn weather once again closes the trails. Yet many return year after year to the wilderness.

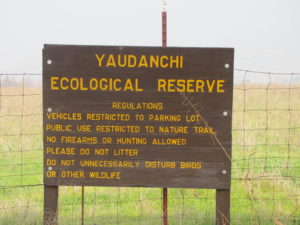

Like all Park employees, backcountry Wilderness rangers are charged under the National Park Service’s mission to preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources set aside by the American people for future generations. Rangers also strive through their visitor contacts to promote appreciation and stewardship of these resources and compliance with the regulations designed to protect them.

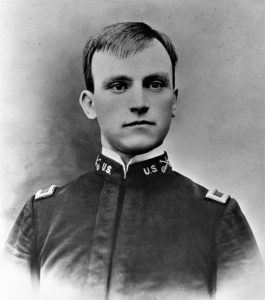

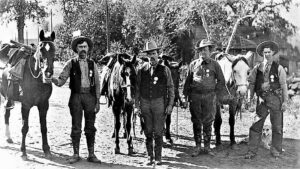

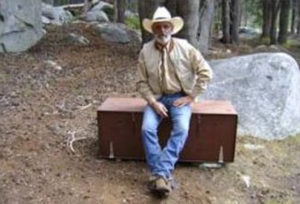

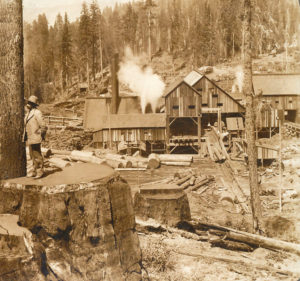

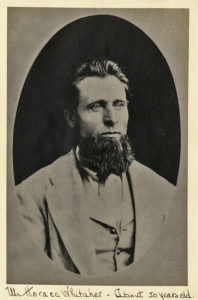

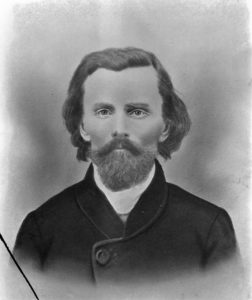

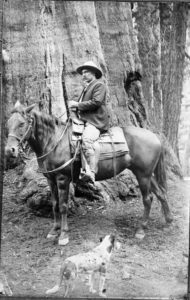

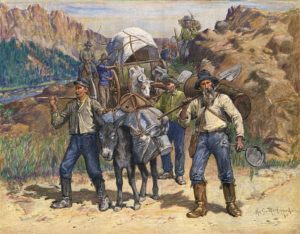

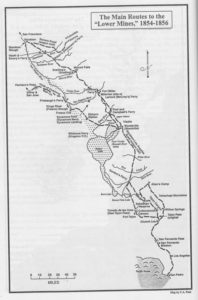

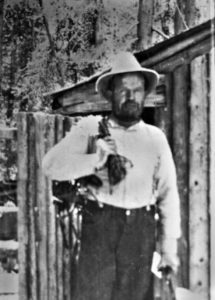

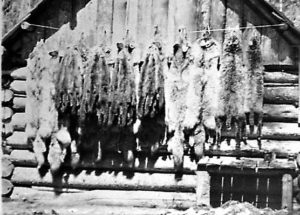

In 1906, when the national parks were still administered by the U.S. Army, prior to the creation of the National Park Service, Captain C.C. Smith, 14th Cavalry, Acting Superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant National Parks, defined the ranger’s qualifications to be “somewhat as follows: He must be an experienced mountaineer and woodsman, familiar with camp life, a good horseman and packer, capable of dealing with all classes of people; should know the history of the parks and their topography, something of forestry, zoology, and ornithology, and be capable of handling laboring parties on road, trail, telephone, bridge, and building construction. These men, in the performance of their duties, travel on horseback from 3,000 to 6,000 miles a year, must face dangers, exposure, and the risk of being sworn into the penitentiary through the evil designs of others.” In addition to the troops, four civilians were working as rangers in Sequoia and General Grant National Parks at that time.

Stephen T. Mather, first Director of the National Park Service (established in 1916), described the early NPS rangers this way: “They are a fine, earnest, intelligent, and public-spirited body of men . . . . Though small in number, their influence is large. Many and long are the duties heaped upon their shoulders. If a trail is to be blazed, it is ‘send a ranger.’ If an animal is floundering in the snow, a ranger is sent to pull him out; if a bear is in the hotel, if a fire threatens a forest, if someone is to be saved, it is ‘send a ranger.’ If a Dude wants to know the why, . . . it is ‘ask the ranger.’ Everything the ranger knows, he will tell you, except about himself.”

Author Eric Blehm describes the diversity of Sequoia’s modern seasonal backcountry Wilderness rangers and their commitment and dedication to their work: “[They] held master’s degrees in forestry, geology, computer science, philosophy, or art history. They were teachers, photographers, writers, ski instructors, winter guides, documentary filmmakers, academics, pacifists, military veterans, and adventure seekers who . . .were drawn to wilderness. In the backcountry, they were on call 24 hours a day as medics, law-enforcement officers, search-and-rescue specialists, and wilderness hosts. They were interpreters who wore the hats of geologists, naturalists, botanists, wildlife observers, and historians. On good days they were ‘heroes’ called upon to find a lost backpacker, warm a hypothermic hiker, or chase away a bear. On bad days they picked up trash, extinguished illegal campfires, wrote citations, and were occasionally called [bad names] simply for doing their jobs. On the worst days, they recovered bodies.

“Park Service administrators often referred to these rangers as ‘the backbone of the NPS.’ Still, they were hired and fired [laid off] every season. Their families had no medical benefits. No pension plans. They paid for their own law-enforcement training and emergency medical technician schooling. And . . . each one of them knew the deal when he or she took the job.”

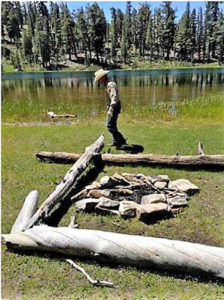

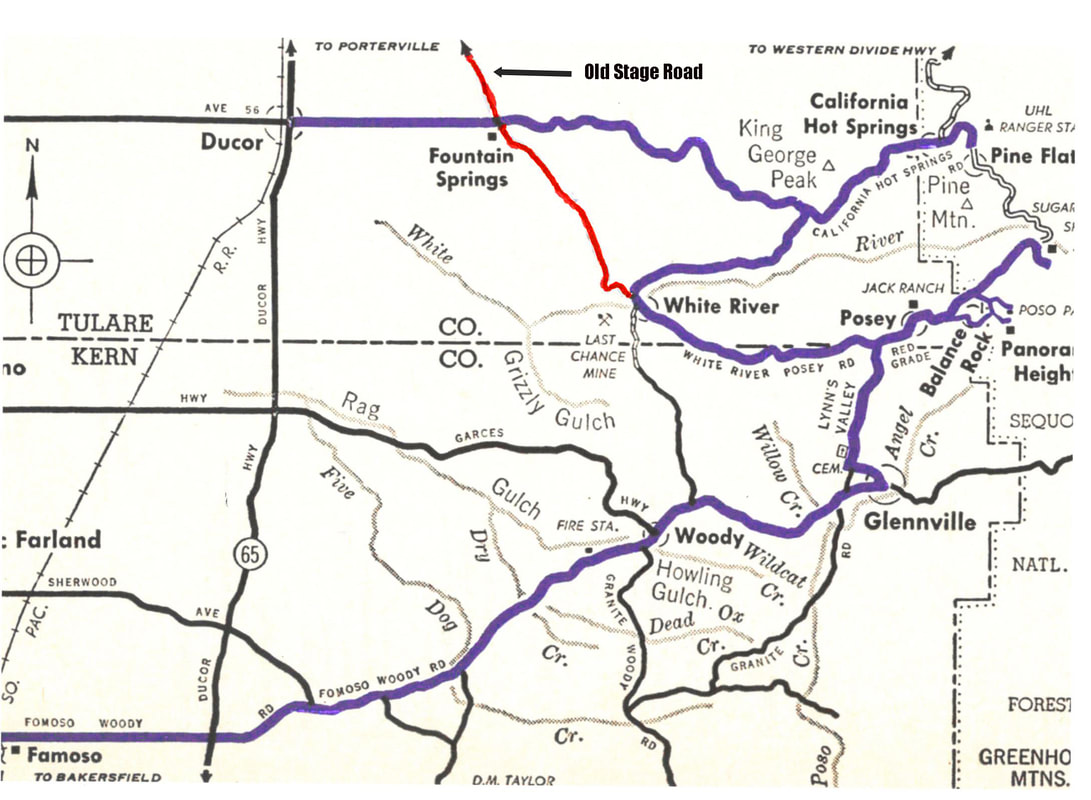

In their end-of-season reports, the Wilderness rangers describe their patrols (miles on horseback, miles on foot, areas and sites patrolled), visitor services (contacts: backpackers, day hikers, park staff, private and Park stock users, and commercial stock users, both spot and full-service trips), law enforcement (contacts, warnings, education, citations). They report on search and rescue and medical incidents, opening and closing times and condition of the ranger station and grazing areas, signage issues, meadow health, and fencing. They discuss natural resources (wildlife, vegetation, water), cultural resources (historic and prehistoric sites, historic structures), and backcountry facilities (ranger stations, barns, outhouses, water and electrical and solar systems), sanitation (campsites, fire rings, pit toilets, “TP roses”), and food storage cables and bear boxes. Other areas covered include supply and equipment inventories and needs lists, aircraft observations, interface with area trail crews, and special projects and recommendations.

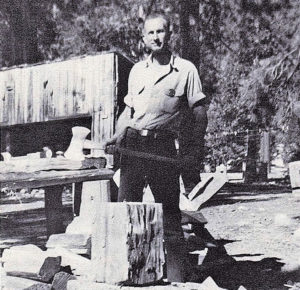

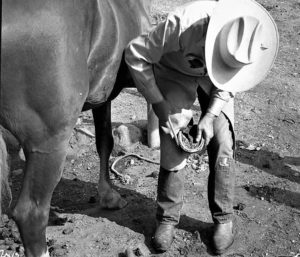

Backcountry Wilderness rangers also do their own cooking, clean and maintain their cabins and barns, trap hordes of invading mice, cut firewood for their cabin stoves, build and repair fences, doctor and shoe horses and mules, help to clear and maintain trails, and assist park scientists with projects such as residual biomass monitoring on meadows. Rangers remove hundreds of pounds of trash from trails and campsites, break up illegal fire rings and restore abused camp areas, look for lost stock and missing hikers, conduct hunter patrols in the fall, and rarely work an eight-hour day, as they are on call as long as they are in the backcountry.

Their work can be exhausting, and it goes on no matter what the weather. Bad weather or trail conditions are often when rangers’ aid is needed most, leading to some longer work days. And yet many of the parks’ Wilderness rangers return for duty repeatedly, as long as they can afford to. They love their jobs and the country they work in. There are hundreds of applicants for each opening every season.

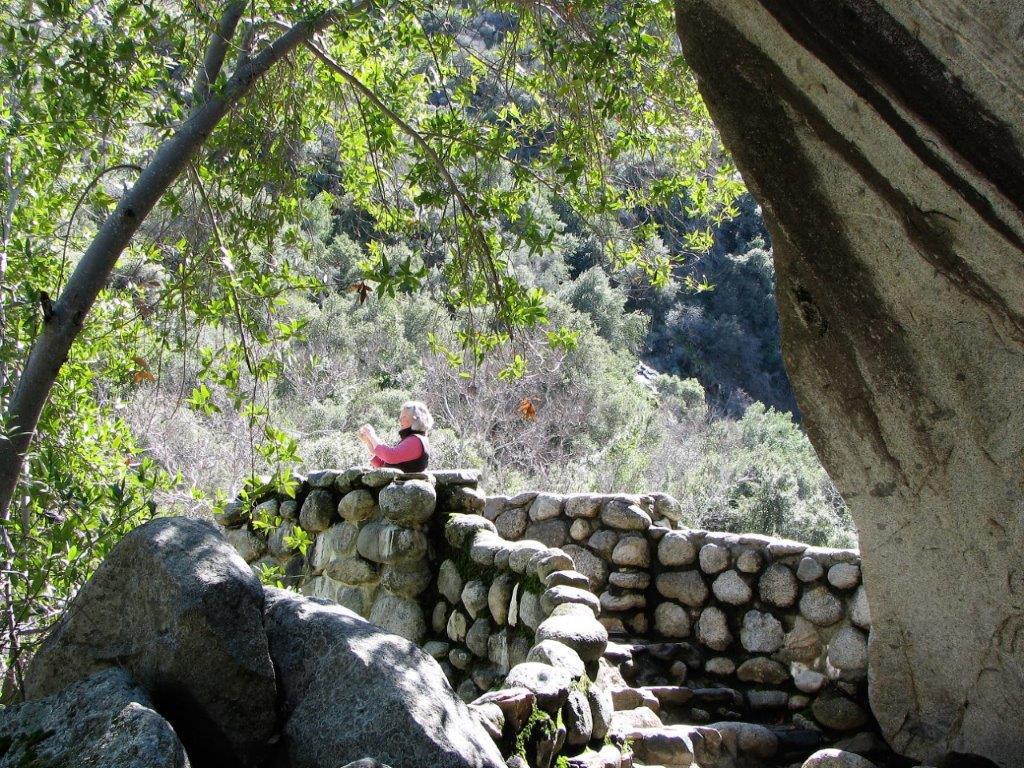

Many cite the beauty of their surroundings, their wholehearted support of the Park Service mission, the pleasure of working with their dedicated colleagues. They care deeply about the health of the backcountry, its lakes and streams, grasses and trees, wildflowers, birds, insects, fish, and animals from little haystack-making pikas to big black bears. They appreciate the opportunity to meet and interact with park visitors, sharing their knowledge of and joy in the backcountry, and keeping the parks safe from the people and the people safe from the parks. And, as Ranger Randy Morgenson said, backcountry rangers get paid in sunsets.

“. . . July and August saw several days each of excellent afternoon thunderstorms complete with hail and strong winds. A family of six . . . were caught in one of the storms as they hiked back from Evelyn Lake to their camp at Hockett. At 6:30 pm the group had still not returned and I went out looking for them. I found the 8 year old and her 13 year old brother running down the trail about a half-mile from the station. . . . I sent these two who were soaked and shivering to the station where I had a fire going. . . . I continued up the trail and located the 10 year old and 16 year old . . . and a few minutes later I located [their parents].

“On the way back to the station I came upon two other backpackers, both soaked and cold. The cabin was crowded that evening with everyone crowded around the stove, drying wet clothing and attempting to keep warm. The trail crew served up some pasta and sauce for everyone and by 9 pm the rain had stopped. The family went to their respective tents and the two backpackers spent the night in the tack shed.” — Joe Ventura, Hockett Meadow Ranger, 2008

May, 2020

” The backcountry ranger job is a very coveted park position and the one in Sequoia has got to be one of the best in the nation. . . . To get the gig, you have to . . . [g]o to USAJobs.com, fill out the resume . . . . score very well on the questionnaire . . . . [Y]ou have to have past experience . . . living in the wilderness . . . not to mention a lot of past time in the High Sierra or a comparable environment. You have to be an EMT, you have to qualify for the GS-5 using education or past government employment . . . . It’s actually a very difficult job to get.” — Chris Kalman, 2015

“I felt connected to people from around the world. I eased visitors into the spirit of the place, offered route suggestions, passed on weather forecasts, repaired boots, supplied a little extra food, or just lent a compassionate ear. Under the open sky, people’s hearts come out to play.” — Rick Sanger, 2019

“I brought my three head of stock into the backcountry on August 4th when the Atwell-Hockett trail was opened to stock. During the season, I patrolled 913 miles of trail. (527 miles patrolled on stock and 386 miles on foot.) I contacted 892 visitors this season. (5 day hikers, 517 backpackers, 6 hunters and 364 stock users with 550 head of stock.)” — Cindy J. Wood, Hockett Meadow Ranger, 1995

” On July 23 two pack mules and an 80 year old male on horseback went off the trail at Cabin Creek, about 1 mile from Atwell Mill. . . . The injured party was carried out by litter to Atwell Mill . . . and flown by Life Flight to UMC. By 10:30 pm I had the equipment, mules, and fellow companion of the injured party out to Atwell.” — Joe Ventura, Hockett Meadow Ranger, 2006

“It was a life steeped in beauty. . . . I woke with the chickaree’s chatter and eased into each morning with anticipation for the day’s adventure, whether a mellow exploration or a grand challenge. The summer’s passing was ticked off by the early season song of the hermit thrush, the bloom and fade of Jeffrey shooting stars, the height of the corn lilies, the late season calming of the stream’s frenzy.” — Rick Sanger, 2019

“The National Park Service preserves unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the national park system for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.’ I stand by that, and I believe it is one of the most important things the United States of America does as a nation.” — Chris Kalman, 2015