Many Treasures are still awaiting their Treasure Tales, which we’ll research and write as soon as time and other resources allow. When their pages are complete, you’ll find them under the Treasure Tales Alphabetized tab. Meanwhile, we’ll be providing basic information for them as quickly as we can here in the Articles Pending section. If you’d like to help to do research for, write, or illustrate these pending pages, please Contact Us!

In 2001, the 1540-acre Dillonwood Giant Sequoia Grove and its historic Dillon Mill remains became part of Sequoia National Park, reuniting Dillonwood with its other half, the Garfield Grove, Park protected since 1890. Straddling the north and south flanks of Dennison Ridge respectively, they comprise one of the five largest of all the Big Tree groves, but the halves have very different histories — privately vs. publicly owned, logged/unlogged, almost unscathed/recently badly burned (NPS is planting restoration seedlings in 2025) — providing tremendous research opportunities and very different visitor experiences, with hope that Dillonwood may thrive anew. Spectacularly diverse Domeland Wilderness, in southeastern Tulare County, offers outdoor adventurers 45 miles of trails (with 7 miles of the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail) into over 130,000 acres of overlapping ecosystems (elevations ranging from 2,800′ to 9,977′) including the Wild and Scenic South Fork of the Kern River, deep gorges, perennial streams, big meadows, pine forested mountains, high desert areas, abundant wildlife, striking granite outcroppings, and namesake huge smooth domes that are magnets for rock climbers, hikers, backpackers, equestrians, fisher folk, birdwatchers, botanizers, and lovers of wild spaces, marvelous night skies, and solitude. The famous Butterfield Overland Mail Stage’s route through Tulare County in 1858 to 1861 included a station at Fountain Springs, where a small settlement arose some time before 1855 about 1-1/2 miles northwest of its California historical marker (#648, erected in 1958). At the junction of the Stockton-Los Angeles Road, followed by the Butterfield stage, and the route south to the gold strikes made in the early 1850s on the White and Kern rivers, the Fountain Springs stop slaked tired travelers’ thirst and offered brief relief from the rigors of the road. At their peak, in about 1940, the historic Giant Forest Lodge, Camp Kaweah, and Giant Forest Village spread 400+ structures through a large part of the Giant Forest, degrading its ecosystem and its visitors’ experience. In 1978, 71 of the most architecturally significant buildings were listed on the National Register of Historic Places. But the park’s 1980 Development Concept Plan proposed removing all this development. By 1999, only three of the historic structures remained, enabling the restoration of the Giant Forest we treasure today. All three survivors are at or near the Giant Forest Museum. Sequoia National Park’s fabulously scenic High Sierra Trail, “the most ambitious trail ever built by the National Park Service in the southern Sierra,” leads you in 62 rugged, up and down miles from lush, giant-sequoia-ringed Crescent Meadow, elevation 6700′, to the all-rock top of Mt. Whitney at 14,505′, the highest point in the lower 48 states. (It’s about 75 miles if you hike on down the east side to road’s end at Whitney Portal.) Built in 1928-1932, this classic, incomparable trail challenges and rewards its travelers with sights and experiences they never forget. Hospital Rock is an excellent stop along Sequoia National Park’s Generals Highway. “Pah-Din” provides panoramic foothill, mountain, and river views; short trails leading to Native American pictographs, bedrock mortars, and cupules; the huge Rock’s “hospital”; a captivating beach and seasonal waterfall beside the rushing Kaweah River; informative interpretive panels; bird and wildlife watching; and picnic facilities, restrooms, and drinking water. For many hundreds of years, Yokuts, Mono, and Tubatulabal people met, gathered, and lived in the large village on this site. Savor, learn from, and remember this beautiful “place to go through.” Readily accessible from four trailheads, Sequoia National Forest’s 10,500 acre Jennie Lakes Wilderness offers 26 miles of hiking trails, beautiful lakes (Jennie and Weaver are the largest), perennial streams, lovely meadows, extensive coniferous forests, rocky peaks (especially 10,365′ Mitchell Peak) affording great views, beckoning spring wildflowers, watchable wildlife, and trail access to Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks’ backcountry (Wilderness permit required for travel into the Parks). Jennie Lakes Wilderness lies almost entirely above 7,000′, so it’s refreshingly cool in summer; winter access is limited by road closures and its steep, snowy terrain. Sequoia National Park’s 39,740 acre John Krebs Wilderness abounds with spectacular scenery, high peaks and passes, sparkling lakes and rushing streams, forests of aspen and conifers, giant sequoia groves, glorious skies both night and day, wonderfully diverse wildlife and wildflowers, challenging trails, and a roller-coaster history including the U.S. Cavalry, vagrant sheep, silver mines, cabin owners, a game refuge, recreationists, lumber and power companies, Walt Disney, environmentalists, a landmark Supreme Court case, and an arduous journey to becoming part of Sequoia National Park and a designated Wilderness. Two campgrounds and pie are nearby! The epic grand finale of the John Muir Trail is its spectacular last 25 miles in Tulare County, all above 10,000′, culminating in summiting 14,505′ Mt. Whitney, highest peak in the contiguous 48 states. This sensational home stretch includes the climb over Forester Pass, at 13,200′ the highest on the JMT, marvelous meadows, numerous lakes and rushing creeks, vast vistas on the Bighorn Plateau, diverse coniferous forests, plentiful wildlife, wonderful wildflowers, precipitous peaks and beautiful basins, brilliant night skies, and soul-filling days in John Muir’s Range of Light. A journey of a lifetime experience. Tulare County’s eighty-six acre Kings River Park is our only park that borders the Kings River and that allows hunting (for doves only, Parks tickets required). It also has a challenging 18-hole disc golf course, an arbor, a restroom, and grass-mowing cattle, but no maintained trails. River access is difficult, but there’s fishing (license required). The County’s 1971 proposed Master Plan for this park included a campground; children’s play areas; picnic tables; arbors, fire, horseshoe, and BBQ pits; a boat ramp; and a caretaker’s residence. Meanwhile, the gate’s locked. Contact County Parks for passes. Owens Peak, at 8,445′, the highest in the southern Sierra Nevada, rises in the center of its rugged 73,767-acre namesake wilderness. Here, the Great Basin, Mojave Desert, and Sierra Nevada ecoregions converge, providing a great diversity of plant life — from desert creosote, yucca, and cacti to numerous forested peaks — as well as two distinct climate zones, plenty of wildlife, vast views, and very starry night skies. Big canyons host springs, oaks, and cottonwoods. Trails include a stretch of the PCT and many use trails, such as peakbaggers’. Hot summers, good shoulder seasons. The Pacific Crest Trail travels about 125 miles within Tulare County, from mile-high high-desert expanses in the south to the trail’s highest point, atop Forester Pass (13,200′), in the High Sierra — living up to its National Scenic Trail designation all the way. With a shuttle set-up, you can hike Tulare County top to bottom (or vice-versa) on the PCT, or you can explore the PCT’s glorious TC landscapes in several shorter segments. If you can’t hike the whole 2,600-mile PCT, you can experience much of the awesome best of it right here in Tulare County. Pixley Vernal Pools Preserve, the only designated National Natural Landmark in Tulare County, is only about four miles from Pixley. Vernal pools were once common in much of our county. They form in shallow depressions in impermeable (hardpan) clay soils after sufficient winter rains. Now vernal pools are rare here because farming deep-rips the hardpan, draining the water away from the surface. Preserved hardpan depressions like Pixley’s hold the water that yields colorful “fairy rings” of spring flowers at the pools’ margins, and the fascinating tiny fairy shrimp, self-burying spadefoots, and other creatures that thrive within them. Burrowing owls, ground squirrels, and raptors thrive here, too. Porterville Historical Museum opened in 1965, in the classic Mission style Southern Pacific Railroad Depot that served the railroad from 1913 until the late 1950s. The museum has changed the historic structure as little as possible while installing a wonderful variety of exhibits, indoors and out, including Native American crafting, Porterville’s Pioneers, farm and fire equipment, Native Wildlife, a Salute to Veterans,and much more, along with special events such as lectures and appraisals, a big annual holiday toy and model train show, ghost hunting tours, and fundraising parties. Porterville’s history is kept alive and growing here.DILLONWOOD GROVE AND DILLON MILL

DOMELAND WILDERNESS

FOUNTAIN SPRINGS

GIANT FOREST HISTORIC DISTRICTS

HIGH SIERRA TRAIL

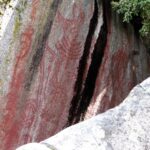

HOSPITAL ROCK, SEQUOIA NATIONAL PARK

JENNIE LAKES WILDERNESS

JOHN KREBS WILDERNESS

JOHN MUIR TRAIL

KINGS RIVER PARK

OWENS PEAK WILDERNESS

PACIFIC CREST TRAIL

PIXLEY VERNAL POOLS PRESERVE

PORTERVILLE HISTORICAL MUSEUM